Scientists have documented an increase in abundance of harmful algal blooms in the Northern Bering and Chukchi Seas. These HABs carry toxins, but scientists still aren’t sure what effect this will have on marine mammals.

“We don’t know yet if toxin levels in Arctic food webs are reaching high enough concentrations to cause health impacts in marine mammals in that (the Arctic) region,” Don Anderson said.

Anderson, a senior scientist with Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, or WHOI, has been studying algal cysts in the Bering and Chukchi Seas for several years. He presented his data and the work of other researchers in the region during a Strait Science virtual event hosted by the University of Alaska Fairbanks Northwest Campus on Oct. 14.

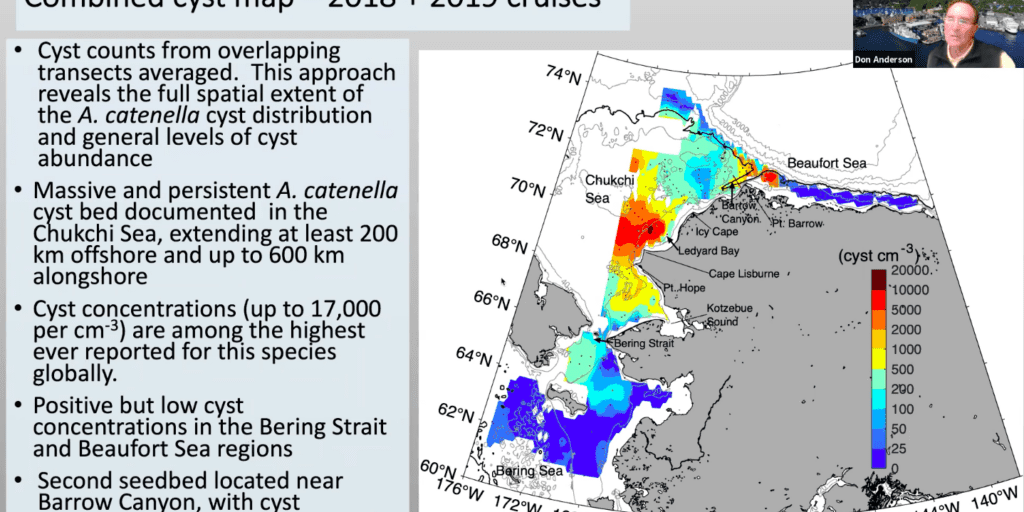

Not all types of algal blooms are harmful, Anderson pointed out. In fact, there are thousands of them spread across the world’s oceans. But in the Northern Bering and Chukchi Seas, there is a growing presence of Alexandrium cysts, an algal bloom that creates harmful saxitoxin.

The previously accepted explanation for how they got this far north is called the “trail of death” hypothesis, Anderson said.

“That (says) it’s being carried from the south in these relatively warm surface waters and that it would form cysts in the Chukchi region, it would fall to bottom sediments where the temperatures would be too cold to support significant germination. … I called that cyst seed bed, a sleeping giant,” Anderson explained.

Since bottom water temperatures have been warming drastically across the Northern Bering and Chukchi Seas over the last few years, cysts are now growing locally in Arctic waters. In other words, the sleeping giant has awoken.

“So what you’ve got then is a dramatic increase in the potential for what we would say is local initiation of blooms. In other words, not just transport, but blooms that are starting, inoculated from that region, from those two Ledyard Bay and Barrow cysts’ seed beds,” Anderson stated.

Recently, the United States Geological Survey concluded that the recurring seabird die-offs seen in the Bering Strait region are not related to harmful algal blooms. USGS scientists did however find low levels of toxins in many species of birds they sampled.

Since 2016, low levels of biotoxins have been documented in all different types of marine mammals, seabirds and various fish species in the Bering Sea, Anderson pointed out.

Even so, Anderson said eating various forage fish or salmon in the region still poses low risk to human health.

“Based on current understanding of these toxins in many other parts of the world, we think that muscle and blubber are not likely to accumulate saxitoxin in levels that pose a human health hazard. These tissues haven’t been fully tested, but there are reasons to believe they’re not going to accumulate toxin,” Andersons summarized.

This baseline is based on the only metric that exists from the FDA regarding safe food consumption of shellfish. It determines the level at which clams or other shellfish become too toxic to eat and then could cause Paralytic Shellfish Poisoning (PSP). However it is not the best way to gauge how high algal toxins can be in marine mammals before causing harm to humans who eat them, Anderson said.

While Anderson believes the health risk for Bering Strait subsistence users is quite low, he still emphasized using caution and safe practices as usual when eating shellfish or marine mammals. He also highlighted the fact that other parts of the world are living with the same conditions.

“Many regions of the world face similar risks and yet are able to maintain healthy communities and ecosystems. But it’s done through good management, good communication, and through understanding what the threats are,” Anderson said.

Overall, as cysts spread and more HABs bloom, there is an increasing potential for them to impact human health and ecosystem health in Northern Alaskan waters. How the marine mammals and people of the region adapt to this remains to be seen.

One observation from Edgar Ningeulook cited in 2013 pointed to an algal bloom near a historical place called Ipnauraq.

“This was the location of a red tide that at one time caused many deaths. And it doesn’t say how, what were they eating? I note that this is a place where there is a lot of fishing going on, especially for herring, one of those forage fish that I was talking about. So was it herring that was eaten, was it clams, who knows. But notice its location, it’s in that pathway of the transported blooms from the south. So long ago there was that threat and it got to the point where many people died,” Anderson summarized.

Any local observations from residents in the region related to HABs or unusual events would help researchers better understand what is happening to the Bering Sea ecosystem, Anderson said. To contact him, call (508) 289-2351 or email danderson@whoi.edu.

More research on HABs in the Chukchi Sea is ongoing. Anderson’s WHOI team will be partnering with scientists on the Russian side of the Strait in 2022 to get the full scope of what other changes are happening in the Bering Sea ecosystem.

Image at top: Map of HABs in the Northern Bering and Chukchi Seas. Provided by Don Anderson of WHOI, used with permission (2021).