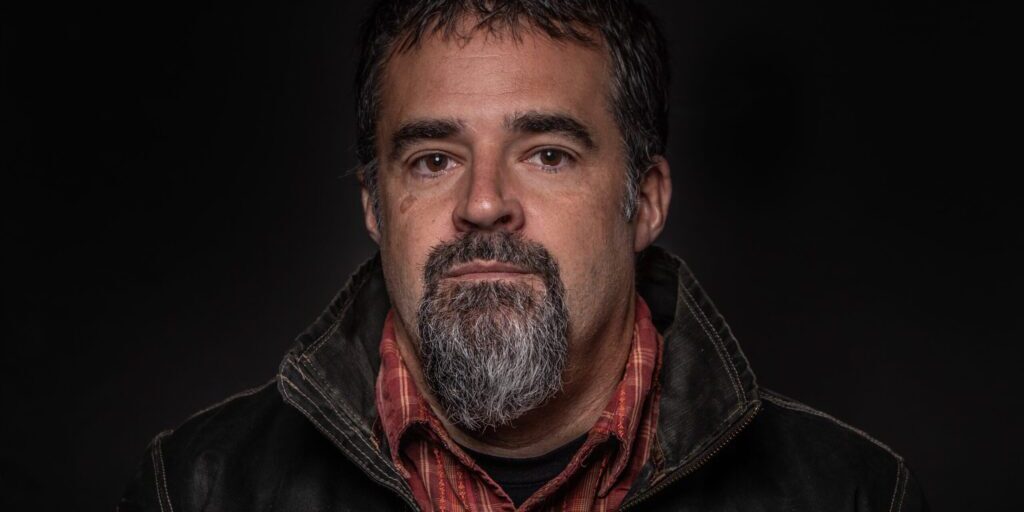

Don Rearden, college professor, author of the Raven’s Gift, and long-time Alaska resident, stopped into Nome last month. KNOM’s Joe Coleman spoke with Rearden about his book and life in Bethel as well as the region.

(As this KNOM Profile begins, you’ll hear the Nome and St. Lawrence Island Dancers perform Raven Dance.)

KNOM: While in Nome Don Rearden had a full list of activities planned

“I’m here in Nome for some creative writing workshops and [to] visit high school students and to read and to present”

– Rearden

KNOM: While he’s currently based in Anchorage at UAA, Western Alaska isn’t unfamiliar to him.

“I grew up in the Bethel area on the Kuskokwim River – a couple villages outside of Bethel – and then went to high school in Bethel, graduated from there. And then, after college in Fairbanks, returned back to teach high school there and so it’s just a part of who I am: growing up in rural Alaska and those moments in the village as a kid I guess really impacted who I was because […] we moved up when I was young but we came up from Montana.”

“So my mom was a teacher, and yeah the economy in Montana was horrible and my parents were just kind of looking for an opportunity – I think they also just wanted to go to Alaska and yeah, they knew somebody there who was part of the district or something and away we came, yeah we moved up. The joke was always my dad was in law enforcement but initially, the first time we moved to the village he didn’t have a job so I think they were just hunting for the school lunch program, you know? Like that was part of what they were doing, and later he started in law enforcement and that’s when we moved into Bethel.”

“[I was] Kind of thrust from Montana cowboy culture into Yupik culture and I was at an impressionable age and really just found myself a student of that culture and then a student of Alaska and Alaska history.”

– Rearden

KNOM: His experience in Western Alaska deeply influenced his writing.

“My parents were already rugged outdoor sort of people, so that fit really well for me – kind of the subsistence life, hunting and fishing and just being outside – and so, all of that influenced me as well as the stories of history and culture and I just became a student of that and I wanted to tell stories and share stories and that drew me into writing.”

“You grow up in Alaska and there’s just these skeletons of history. Driving around Nome that’s clear, you just have old equipment, and as a kid you either just wonder how that got here or you don’t and I was one of the kids that wondered about that like ‘how did that get here?’ or ‘why is that there?’ An example of that would be in one of the villages I lived in, across the river there were some abandoned houses and it was as if time was just paused in those houses and I wanted to know why and later would learn that was just part of the epidemics came through and so it was like ‘well, what about those epidemics and what’s that all about?’ and so I think just being just being aware of my surrounding and asking questions is just where that started. It was instilled in me from my mom too. Even in Montana where she grew up, she was really interested in the Blackfeet and the tribes of Montana and I think that rubbed off on me for sure. Just wanting to know the real history of the place and not that stuff that’s in the textbooks.”

“We’re lucky, those of us that get to get raised in a place where the culture is still alive versus so much of the rest of the world where modern culture just absorbs enough and just destroys the elements of real, true culture that get passed on and so I think that’s something that I’ve really been fascinated with and found myself more just trying to figure out who I was and what place did I have. Even for a while, while I was in high school, I was kind of pretending that I kind of had this Irish culture, because that’s my background too because my family is Irish, but really I didn’t learn anything about Ireland or what it means to be Irish and would pretend that somehow cheering for Notre Dame would connect me to my Irish roots, you know, just the silly things high school students do and not fully appreciating what I had learned and then also the importance of some of the knowledge that had been passed onto me, whether it was from elders, or people who had learned from elders, or just from observing and paying attention, so that’s definitely kind of imbued in my writing and who I am as a human being and as a teacher, then I move to a place like Anchorage and feel like I don’t have a culture”

– Rearden

KNOM: Rearden is far from taking his upbringing for granted.

“What I’ve been given is a gift, in my upbringing, and so I do feel lucky that way where I think just a lot of people feel displaced, whether their heritage is from Ireland or Italy or one of the many indigenous cultures in America that have lost like the real roots of that culture and I think that’s part of it.”

– Rearden

KNOM: While there was definitely an adjustment period, Rearden said he felt at home in Bethel.

“I felt welcome. I never had anybody tell me to go away or that I don’t belong there or something. And if there was a circumstance like that, I understood and probably agreed with it.”

– Rearden

KNOM: Like his mother, Rearden spent time teaching in Alaska himself before transitioning to the University of Alaska Anchorage.

“Well for me it’s different because growing up here you just experience that constant churn of educators who have no clue about Alaska, you know they’re always outsiders coming in and so I saw that early on. I mean, we were a part of that and then we stayed, and my parents raised our family there. And you would just see this constant churn – even at a certain point, the people that have spent constant time and live here, they’ve experienced the same thing where you just pour all this energy into outsiders and they leave, and then another group comes in and you pour all this energy in and they leave, but the people that stay slowly learn that too. So there’s an educational process there, and as an educator, just knowing that, I felt like it was my job to come back and teach and to inspire a next generation of teachers, and I’ve taught long enough that I’ve seen that come to fruition. It’s really neat to see students that I taught in Bethel who are now teachers, and I can go in and sit in on their class and they’re actually teaching my book or something, you know, it’s really neat. So I feel fortunate to come full circle.”

– Rearden

KNOM: Now that he himself is an educator and a writer, he has found unexpected worth in his work.

“I think there is an element of ‘what does success mean?’ and for me as a writer, or I guess from the outside world, success in publishing is selling a ton of copies, you know, and making the best-seller list and getting critical acclaim, and with the book initially I couldn’t even get it published in the US and so there were just these ups and downs that hit me, and even when I did get it published in the US and I landed a huge review in the Washington Post, I thought it was about that sort of success, and so where I didn’t sell millions of copies, what I realized was the intrinsic success and I never could have guessed. I mean, all I wanted from home – the Bethel region, or at least rural Alaska – was to be able to go there safely. I was worried [about] that. Some of the stuff in the book is really dark and horrible, and I was afraid I wouldn’t be able to go home, and instead it’s taught in the schools; and so that to me is the most beautiful thing and probably the best reward out of it, and so to see someone I’ve taught in high school and she’s now teaching it in classes, it’s so beautiful and so powerful.”

– Rearden

KNOM: If his readers could get one thing from his book The Raven’s Gift, Rearden hopes they take away a sense of the importance of memory.

“Yeah Alaska has this really weird ability to forget history and not teach history in a way that is compelling enough for people to live here, and I think that might be part of the whole transient problem – people coming and going – and so no one knows what actually got taught or if it was worth teaching and so we just forget. I guess amnesia is the word, just this weird amnesia. I think it’s two-fold, so I want people to learn a little bit about Alaskan history so we don’t repeat the same mistakes as in the past, maybe when it comes to epidemics and some of that. I think maybe more importantly, really getting at the idea that especially in rural Alaska where women and children have been mistreated for so long, that we have to focus again on elders and the children and the culture. I think the indigenous cultures of Alaska thrived here for millennia and it wasn’t that long ago, so we can’t forget that and we have to find a way to bring that knowledge back because we need it again and in a big way with the changes that are coming, whether it’s climate change or whatever’s on the horizon, that knowledge was important, and so if there’s any message in the book it’s that we can’t lose that knowledge that we have left and we need to revive what we can.”

– Rearden

KNOM: Rearden says he considers his experience a fortunate one.

“I was really lucky to be isolated from so many of the bad things, you know, that happened in rural Alaska because I had a loving, caring family and a loving caring community that isolated me from some of that.”

“Then at the same time, the impact of loss is just catastrophic, like on a level that is just hard to talk about and make sense of for a lot of people, but I know the listeners out there would understand it too, you know? The rest of the world doesn’t know, for instance, the suicide epidemic like we do where I cannot even count how many people I know who I’ve lost. I tried it at one point, I tried writing a poem about it at one point, and the number just got mind-boggling. I started with a teammate from high school, a basketball teammate and then his loss. […] when he died we stole his jersey, I stole his jersey to give to his father who lived in a village outside of Bethel and the coach was really mad about that. Ran us all until we threw up. Nobody ratted me out and so that was kind of a high and low point of that, to lose a player like that. So even when I was trying to capture it in my writing, I realized that the image I had was that I lost so many people just to suicide that it was no longer this ghostly jersey anymore, it was this whole tournament of people and all the way to the coach level. It wasn’t’ just teammates and players, it was people really close to me, and so I guess – and I’m sure people out there can identify with this – you lose so many people to something like that, you become desensitized to it, and that to me is a really sad thing. As a writer and as an educator who’s in touch with my emotions, to realize that, to be able to even say it, that I have almost no emotional response when I hear about a suicide because it’s just happened so much. And to me, that really says a lot about where we’re at in Alaska that we don’t do enough of that. Now we’re trying – I’m part of lots of groups who are trying – to figure out something, a different paradigm I guess, in terms of the suicide epidemic. For me, we wouldn’t talk about it. You would lose a classmate and the rule was you just don’t talk about it. So the classmate isn’t there, everyone knows what happened and no one talks about it. That’s not a healthy response. Then it’s gonna happen again and so I think it’s really about some sort of paradigm shift that we have to have happen in Alaska. Yeah, I don’t know, it’s an answer that I think is actually maybe rooted into delving into some of the answers from the cultures.”

– Rearden

KNOM: Overall however, the unique aspect of life in Western Alaska is something Rearden is grateful for.

“It’s community. The idea of a village. We throw that term around as just a place designator but really it’s about community, and the village concept is a powerful, powerful notion where you feel like you’re a part of something that’s more important than you; it’s not just about you. I think that’s a really neat idea. And it’s what we’ve lost, that you know your neighbor, you know what your neighbor needs and you know when your neighbor needs help, and you leave and go to a place even like Anchorage and for the most part, people don’t know their neighbors; not on a level like we do here in rural Alaska. So that’s part of it, you just know that people have your back. And that’s part of it, to just know that you have a whole community of people that will be there for you is really something else. I’ve been fortunate myself. There was never anyone from my communities when I said I was gonna be a writer or I just started doing the writing thing, there was no one that didn’t support me, and that’s from when I was a little kid. So I felt that support and I still do. There’s people that are so proud and I’d hear people trading and exchanging goods for a copy of my book or something and just that feeling alone is really great and it helps me navigate living say in a place like Anchorage because I joke that I have little Bethel in there. You know, the people who moved from Bethel and live in Anchorage, we’ve still been able to retain that sense of community, and I know those people will help me at the drop of a hat, and we do that with each other. Somebody needs something, we’re there for them, and that’s just the beauty of rural life, I think. People outside really have no idea, and I’m sad for them for that really.

– Rearden

Image at top: Don Rearden, author and UAA professor. Photo courtesy of Marguerite La Riviere (2019).