This year, the Society for Science and the Public awarded nearly $350,000 to only 66 teachers mentoring students from underserved populations around the country. One of those teachers is Dr. Anthony Husemann, a full-time science teacher at Nome-Beltz High School. Dr. Husemann received $5000 in grant money to serve as a mentor and advocate for Nome students to be able to conduct science research independently, as well as to develop STEM projects that can then be entered into science research competitions.

Dr. Husemann has been an educator for the past 15 years, only a few of which he has spent in Nome. But this grant will allow him to give back to Nome students in a transformative way.

KNOM: Well, congratulations! How did it feel when you found out you’d be receiving this grant to help support STEM research for Nome students?

Husemann: I was immediately very excited. They only gave this grant out to 66 teachers in all 50 states. So, there isn’t a huge pool of people who got the grant, so you know, you feel kind of good about the fact that you got what amounts to a very special award. There are millions of teachers in this country, and I’m sure hundreds of thousands applied for the money. But I was more excited about what it [the money] could do than the fact that I got it.

Initially, it was a $3000 grant, but in part, because we are not going to be able to attend conferences where usually they would pay you to fly in and meals and all that, we’re doing everything virtually. Instead of saying “Oh good we’ve got all this extra money,” they [The Society for Science and the Public] actually took that and turned it over to us. So, now the grant’s a $5000 grant, so it’s even better than it was to begin with.

KNOM: What specifically do you hope to use this grant money for as it relates to these at-home STEM research and projects for the science fair?

Husemann: Well, they are making a whole host of what they are calling “research lab kits” available to us for use at-home or in the classroom if the students are still here, so either way, we’ve got it. This gives the students the autonomy to focus on their own unique interests, whatever that research is.

We’ve got chemistry kits, something called a neuron spiker box bundle, water sampling, weather equipment kits, and more that are available to us. The kits might be like $50 to $60 a piece normally, but we won’t have to pay for them. That means, at least in my chemistry class (I have 13 students in there), I’m going to have a kit per student. And I’m going to purchase a whole bunch of these chemistry kits because otherwise, I wouldn’t have them.

I don’t have to use them in the room; in the room, I’ve got lots of equipment, but let’s say we’re forced as a… Well, one other local district is now having to close their schools, so it’ll give us that option if we get stuck in that position. And there may be students in other grades (I also teach physical science which is both physics and chemistry), there might be students in the 9th grade who couldn’t do anything unless they could do it at home. So, I’ll have the option to give them that and get them doing something at home too.

KNOM: Right, and I mean, not only is just having the equipment important, but also having increased access to mentorship and advocates like yourself for these projects in STEM-related fields. Undoubtedly, that really instills a sense of comfortability in the student.

Husemann: Yea, and the organization (SSP we call it for short) is not just giving us a grant. I spent 9 hours over the weekend attending a virtual conference, and most of it was fantastic. It was people sharing with people the resources, the equipment, the personnel, the ideas, and the processes and procedures they’ve used to get successful entrance into even national level or international level science fairs. And when I say successful, I mean students who developed patentable products as part of the process, and it’s just amazing the simplicity of some of what kids do. And when you see a teacher show you what this kid did, you go, “that is such a fascinating idea, I’m sure somebody in my school can expand on that.” So, it’s professional development for me that also will enhance my instruction and the kids’ ability to perform in these science fairs.

KNOM: And what do you think are the sort of wider effects for students who might not otherwise have this greater access to STEM instruction and the ability to pursue and execute these projects?

Husemann: I can envision probably… something that comes out of my (I’m teaching a class on personal finance), and this comes out of my personal finance course: I said to the students today, “I’m gonna bring you another two or three or four copies of the Nome Nugget, and I want you to note what jobs are always available.” And every one of those jobs that’s always available has to do with the hospital [Norton Sound Regional] or the clinics out in the villages. We need a lot more local people willing to take those jobs, so we don’t get this itinerant effect of, you know, somebody’s in here for two weeks and they’re gone. That happens all the time.

A wonderful spinoff of this would be if students became so interested in science and in bioscience and biomedicine and medical science through it, that we get a significant number of new CNAs, nurses, and PAs, etc coming out of our own school system. And we’re not getting a lot of that. But I think that this could be part of that process beginning because they’re aware of the science, and their skills are sharpened, they don’t feel so intimidated about going into it. Because, you know, let’s face it; medicine is intimidating. The hope would be that we can create a cadre of young scientists coming out of the high schools who go to universities and come back to our communities and serve them.

KNOM: And, I mean, it feels much more rewarding, and it feels much more practical to apply the things that you’re learning in your own home. Then, it creates that sort of interest and you feel more capable in that sense. Because you can do all of these things in a classroom, and that’s wonderful… But having the ability to do it outside of the classroom makes you feel a lot more secure.

Husemann: Yea, and they’re good at that. This whole grant is, for example, advocates will have a choice of using their funding for hotspots or some form of internet access. In the end, we may be able to use some of these grant funds to get access for students who don’t have it [internet access] right now.

So, I’m going to be looking at that. If we end up going out of here, and there are key students, especially among Native Alaskan students because this organization is devoted to educating Native or Indigenous peoples around the country… I want to be able to get them that access, and I think people would be pleasantly surprised if they went, “what do you mean, you’re actually going to be able to pay for our internet?” Well no, not me, but this grant is. It’s something I really hope will come to pass if we need it.

KNOM: It makes such a huge difference, especially now. And that kind of leads into my next question; you’ve been an educator for decades, and you’ve kind of seen how we’re transitioning now into a greater virtual model. How has your experience prepared you for the “challenges” presented by the pandemic as far as learning goes?

Husemann: Well, out in the community, my experience started online in 2001. I was writing computer-assisted instruction programs way back in the early 1980s, but that’s as far as we were going – there was no internet, you couldn’t go online. But, when I took a doctorate, it was all online, with the exception of the residencies that were required, and they were required because the brick and mortar schools, the big, you know Harvards and Yales [said], “we will never go to online education,” and they were standing steadfast against it. Well now, per force, because they have to… they discovered online education.

I did a doctorate; it took me five years that way. Then, I started teaching in 2006 as soon as I finished it, for a university online. So, I’ve been teaching for them now for 15 years, and I am very comfortable with online education and the paradigms and the necessities to always make contact with people. So, if you don’t make contact personally, online education will have a lot of kids get lost.

KNOM: So, what are your suggestions for how the community or individual families can support students as we transition to in-person learning, but also, in the event that we do have to go online, how should we be supporting our students in this context?

Husemann: I used to be a principal in the Cayman Islands, and one of the happier days was always the kindergarten graduation, and I would say to the parents of those kids, “don’t forget these kids when they get this big,” because we always had high school kids assisting. Because what happens is they grow up, they grow more distant from you, and you naturally let them go on their own in certain ways, and there’s nothing wrong with that.

But don’t forget to check up on them. Call the school. Talk to their teachers. We’ve got PowerSchool that anybody with a cellphone can access… Check their grades yourself; don’t wait for the midterm! And when you say, “how are you doing in school?” and they do, “oh, okay…” Well, you know, hey I believe you. But, was it Ronald Reagan who said, “Trust but verify.” (chuckles) You know, verify that! And don’t castigate them when they aren’t doing well, find out what’s going on because a lot of times they may just be lost, and all they really need from a parent isn’t abuse or discipline. They need encouragement, and they need you to know what’s going on, because when you do, you automatically show them you care. And it’s as easy as a phone call, an email, a text message, check the PowerSchool, send a note to a teacher…. I guarantee you won’t get an attitude out of us. Our reaction is going to be, “let me check up on that and see if I missed something.” I want to make sure the students do well, and so does everyone else here. So you can’t assume learning occurs because a kid(s) is in a room; we don’t, teachers are always checking. Parents need to do that too. Check up on them, see how they’re doing.

The science research competition is scheduled for early March in Nome. Whether the competition occurs in-person or virtually, Dr. Husemann plans to use his $5000 grant to equip Nome students with plenty of resources and tools that can help them thrive in and outside of the classroom.

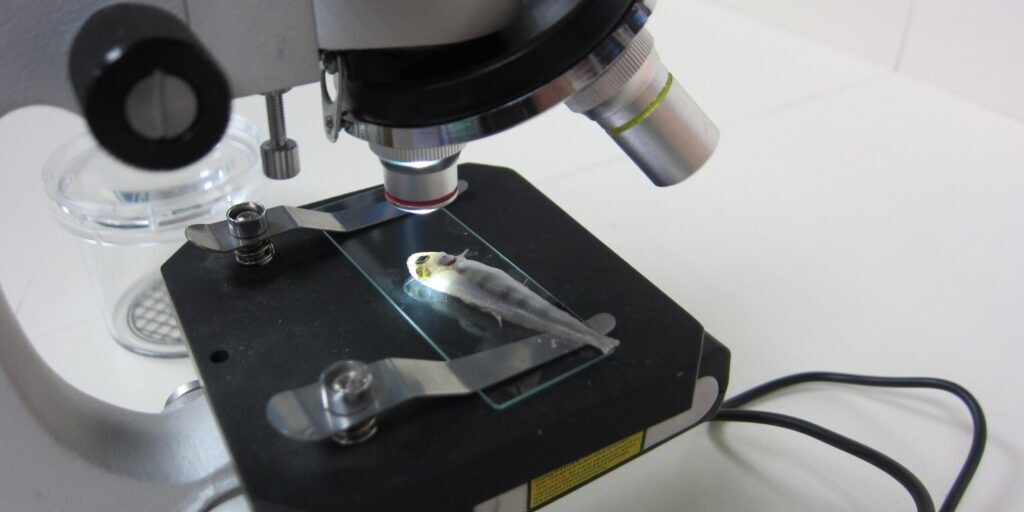

Image at top: Silver salmon fry under a microscope at Nome Elementary School. Photo from KNOM file (2014)