Salmon abundance is down and population distributions have changed, according to NOAA’s 2021 surface trawl survey. Besides focusing on salmon, the survey also examined aspects of Bering Sea life such as zooplankton, sediment, sharks, marine birds, pacific herring, capelin and saffron cod.

Like the bottom trawl presentation that occurred via Zoom earlier in November, the top trawl presentation examined decreasing fish populations occurring in several Bering Strait species.

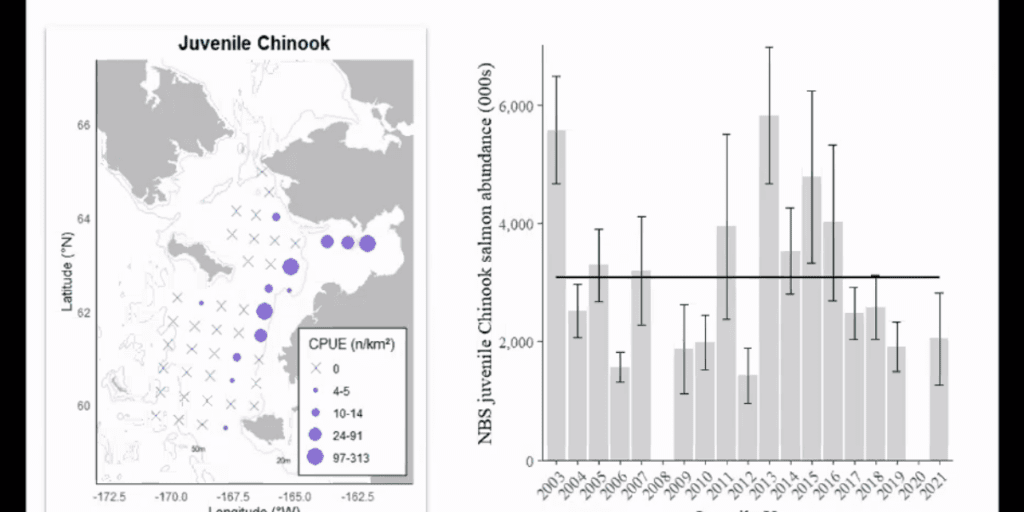

According to the survey’s preliminary estimates, young Yukon River chinook salmon populations continue to be low.

“Juvenile abundance was below average in 2021 and has been below average since 2017,” Research biologist Jim Murphy said.

Besides lower populations, Murphy also noted the distribution of chinook salmon observed this year was unusual. While one typically finds chinook salmon distributed throughout the Bering Sea area, the area which NOAA typically surveys, most chinook salmon were found near Alaska’s shores.

Like chinook salmon, Murphy’s team observed chum salmon almost exclusively near Alaska’s shores.

“And this is even more atypical for chum salmon as they tend to be much more broadly distributed than chinook salmon,” Murphy said.

Juvenile chum salmon populations have actually been above average since 2018, according to Murphy. 2021’s population is estimated to be one of the largest juvenile populations seen since then. A large juvenile fish population usually correlates with a large returning adult population. From past observations, however, the correlation between adult and juvenile chum salmon tends to be more variable than the relationship between juvenile and adults in other fish species, Murphy said. To illustrate, he pointed out that there was a large population of juvenile chum salmon in 2016, but a significantly low adult population. Murphy and his team postulated that this is because chum salmon are dying at greater rates later in their lifecycle. This would explain the great decline of chum salmon in the Yukon river, in spite of the high juvenile populations observed in the survey, Murphy said.

Pink salmon saw the same kind of low numbers and near shore distribution during 2021. Murphy noted that his team combined pink salmon from Norton Sound and the Yukon river into the same graph, due to their genetic similarity.

“With this model we are expecting to see low numbers of pink salmon returning to the region in 2022,” Murphy said.

In contrast, NOAA’s preliminary biomass index of coho salmon was close to the highest in the history of the survey. Hopefully, this means a strong run of coho in North Bering Sea salmon next year, Murphy said.

Besides salmon, multiple fish populations surveyed were found to be lower than average. These species include capelin, saffron cod, young pollock and cod and pacific herring. In general, forage fish populations are low.

In addition to examining small fish populations, 2021’s surface trawl survey tagged salmon sharks in order to better understand their migration habits. Most information available on salmon sharks is based on female sharks, Murphy stated. The fact that the surface trawl survey has been able to tag three male sharks to date has been particularly helpful. Two of the sharks tagged in the Bering Sea, eventually returned to the Bering Sea in the summer possibly indicating that the Bering Sea is an important summer habitat for sharks, Murphy said.

In regards to seabird observations, the last part of the surface trawl survey, Murphy and his team saw fewer dead seabirds than in past years. However, it is difficult to spot dead birds from a moving ship, Murphy said.

NOAA conducts both its bottom and surface trawl surveys annually to study the status of marine life in the Bering Sea.

Image at top: Graphs on juvenile chinook salmon. Photo courtesy of NOAA