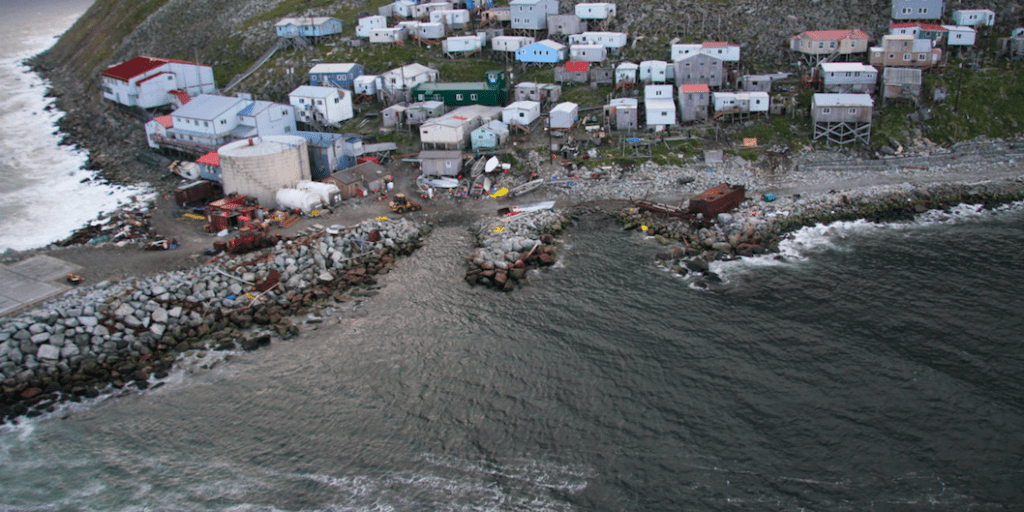

Following changes in climate variability, one University of Alaska Fairbanks assistant professor has discovered surprising changes in the Little Diomede auklet population.

Working at Bethel’s Kuskokwim campus, Hector Douglas has been studying the crested auklet’s fluorescent pigment for more than a decade.

His most recent study on the pigment started in the summer of 2015. Douglas describes the sea birds that year as normal, saying, “the crested auklet is a bird you can hold in your hand. Overall, the body is a dark grey, a little brownish in the plumage, and during the breeding season, it has these bright orange bill plates.”

The next year, in June of 2016, when Douglas came back to finish his study, other changes in the population took hold of his attention.

What he saw was an unusual sight for the month of June. Attendance at the crested auklet’s breeding colonies had dropped by 35-50% from the previous year [2015].

In Douglas’ experience, crested auklets arrive to the island in June with bright orange bills, a signal that they’re ready to mate. But last year [2016] , the birds were coming later than expected, and their bills weren’t fully orange. Douglas doubts that these late-comers, who lay a single egg per season, could breed successfully.

“And to see those birds arriving in the latter part of July with this not fully acquired coloration suggests that these birds were distressed in some way,” says Douglas.

Auklets can cope with difficult conditions, like those that would spur a delayed arrival, by secreting corticosterone, a hormone that helps the animals mediate stress of certain types.

“And by ‘stress,’ I mean things like your energy balance.” Douglas adds, “And the amount of energy you need to mobilize from your fat stores to cope with the demands that your body requires.”

The corticosterone levels in auklets can give scientists a look into other facets of their life. In this instance, by looking at the hormone, scientists like Douglas can get an idea of possible nutritional stress the auklets may have experienced. Compared to the 2015 auklets, Douglas found an increased baseline corticosterone paired with a decrease of the carbon-13 isotope in blood samples. This suggests a decrease in zooplankton that auklet diets specialize in. When faced with a lack of their favorite food, rather than move onto a different type of food, Douglas thinks that the auklets may have varied their diet to include less nutritious zooplankton. But a lack of easy food availability can halt normal breeding activity. And in the auklet life cycle, Douglas says, consistency and good conditions are important.

“In terms of looking at a population, it is important to have successful years. So, what we need to be concerned about, if we’re continuing to see warming trends, how is that going to impact birds in terms of breeding? They have roles in nature, but they also supply humans with food.”

Douglas suspects the changes seen in the population may be related to variable changes in climate. In 2016, it was reported that a particularly strong surge of above-average temperature water called “the blob” also contributed to a mass disruption of Alaskan marine life.

And while experts may not be reporting a “blob”-like event this summer, National Weather Service climatologist Rick Thoman says current waters in the Northern Bering Sea have taken a departure from normal conditions.

“With summertime here, and the Alaska current flowing now bringing water from the Northeast Pacific into the Bering Sea, we’re likely to see those above-normal sea surface temperatures continue into the fall months, at least.”

The possible effects of these water temperatures on the 2017 auklet population are yet to be studied.