As average temperatures rise, two University of Alaska Fairbanks researchers are mapping permafrost’s impact on Alaska. Vladimir Romanovsky and David McGuire are members of a team working to identify worldwide regions susceptible to thermokarst.

Romanovsky says the natural process is the result of what happens when ice-rich permafrost begins to melt. “The water may run away or stay in place, but because of that, surface of land is subsiding. This subsidence could be pretty substantial if permafrost is ice rich, and this subsidence of surface develop features — thermokarst features,” he says.

After the thaw, the area affected could erode to form gullies, lakes, or any number of other geographic features. Furthermore, normal erosion could make for even deeper gullies and possible drainage from existing lakes. For Alaska’s wildlife, Romanovsky says those consequences are a mixed bag. “For birds who use lakes for living, that development will be good. It may be not so good for caribou, so there will be some losers and winners of this process. The definite loser is infrastructure,” he emphasizes.

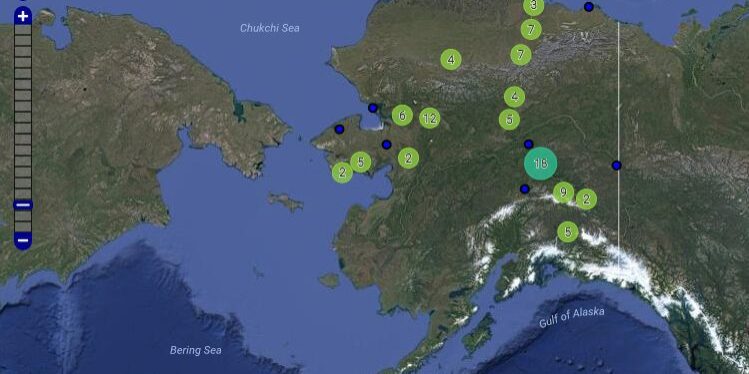

The map suggests communities in the Yukon Delta and the North Slope regions are most susceptible to change. Those regions could see a transition towards an increased amount of wetlands. McGuire thinks the map can help developers during those transitions. “If you overlay this, for example, where villages occur or where other infrastructure occurs, you can get a general handle on the amount of infrastructure that’s susceptible to thermokarst disturbance. Some of this infrastructure has been put in with the assumption that permafrost will remain relatively stable, and if it does degrade, there will be consequences for maintenance or replacement of infrastructure.”

Romanovsky says consequences to infrastructure add to the threat that thawed permafrost already provides. “A part of this process will be development or release of carbon dioxide and methane and possibly other gases into the atmosphere and increasing the amount of greenhouse gases.” He adds that permafrost holds twice as much carbon than what the atmosphere currently has, and says the release process will be slow, estimating decades or more before the full effects are seen.

The researchers’ map claims that twenty percent of the globe’s northern permafrost faces a potential threat from the natural process. The thermokarst landscape map is available online.