Reindeer herding is becoming an increasingly attractive economic option for communities in the Norton Sound region. As winter sea-ice cover becomes more unreliable, the traditional practice of hunting for marine mammals is more dangerous.

Some community leaders hope reindeer herds, originally imported from Scandinavia in the late 19th century, could now fill a growing gap in ensuring economic security.

KNOM’s Gabe Colombo has the story of three Norton Sound communities working to expand their operations.

I’m about to step inside a mobile reindeer processing plant in Savoonga with Richmond Toolie, the chief herder of St. Lawrence Island’s four to five thousand reindeer.

“My uncle Herman — I followed him when I was a teenager, and he taught me everything, while he was the chief herder. I enjoy doing it. I love it. I just go out there and drive all around the island.”

The plant is owned by the University of Alaska–Fairbanks and has been here for four years, and Greg Finstad with UAF’s range management program has trained 22 Savoonga community members on how to use it. The plant is basically two big trailers with equipment inside to store, cool, hang, and butcher 16 reindeer at a time.

“Before we band-saw them, we cut them in half right here, with a chainsaw. Hang them up and cut them right in the middle. We have orders from all over Alaska and Washington.”

Those orders, and others, from as far away as Australia, have convinced Savoonga tribal chief Delbert Pungowiyi that the demand for commercial meat is there.

“To us, that’s the only real promise that can really bring a huge difference to our people on the island: where we can sustain ourselves and take care of ourselves as our ancestors have, without pleading to Washington or anyone for any funding.”

Right now, they’re limited to field slaughtering, which Pungowiyi estimates brings about $1,000 per whole carcass. But butchering it professionally, he thinks, could get at least $1,600 per reindeer.

To do that, though, they need to pay for a U.S. Department of Agriculture representative to come inspect the processing facility. They also want to build a permanent processing plant, a new corral, and new roads to make herding the reindeer more efficient.

Pungowiyi says the Native Villages of Savoonga and Gambell are seeking funding from the federal government and elsewhere for these projects. They’re also working with Kawerak, the regional nonprofit corporation, to develop a business plan, and lobbying Senator Lisa Murkowski to come visit and discuss the project.

“Really need to get that in motion because of the food security that we’re losing from the Bering Sea itself.”

Across Norton Sound, in Stebbins, Thomas Kirk feels the same way. He’s the clerk for the community’s tribal association.

“Climate change has affected our sea-ice hunting and our marine mammal gathering. The ice is a lot thinner. And having our reindeer is a blessing.”

The herd here is estimated to be over 5,000 head, the largest in the Norton Sound region, and it’s jointly owned by the Native Villages of Stebbins and St. Michael and the chief reindeer herder, Theodore Katcheak.

The group is already selling antlers commercially, to a buyer from California, who resells it to Asian-Americans for traditional medicinal purposes, at $25 a pound.

“I also have other interests in the Asian market that would like to purchase the horns and the meat: Eastern Asia, China, Singapore, Hong Kong, Japan.”

Kirk says the triparty group wants to work with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to do an aerial survey of the reindeer, to figure out exactly how many are out there and how healthy they are. They’re also hoping to have the mobile processing plant transferred from Savoonga to Stebbins and St. Michael.

And as Theodore Katcheak, the chief reindeer herder, tells me, the free-range meat is healthier than the reindeer we find in the freezer at the St. Michael grocery store.

“The color of this meat is dark, because they’re probably feeding in the overgrazed areas.”

The meat is also a reliable food source for the communities’ residents as marine mammals become less easily obtainable.

In terms of commercial sales, Katcheak says there’s still a long way to go, for the region and for him, personally.

“I see that Sami people — they know how to handle reindeer. They’ve been doing it for many centuries. My age, I’m 70 years old, I’m just like a little baby just waking up; I don’t know what to do. You don’t see no 20 or 30 herders in Alaska. You only see like five or six, maybe seven herds.”

Pungowiyi in Savoonga hopes to change that, by taking reindeer from St. Lawrence Island and reintroducing them to communities like White Mountain that lost their herds to encroaching caribou.

Pugowiyi envisions a coalition of reindeer-herding tribes around Norton Sound that could sell meat collectively, with a central processing plant and freezer in Nome, something the regional Reindeer Herders Association has discussed.

“If we did it right, we could become Alaska’s reindeer capital: the Bering Straits region.”

From Savoonga’s shoreline, the bright-blue water stretches as far as the eye can see on a sunny July day. As late as 1975, though, you might have seen some sea ice here at this time of year. Now, solid sea ice isn’t a guarantee even in March.

But if Toolie, Kirk, Katcheak, and Pungowiyi see their vision of a reindeer economy made real, a more solid guarantee of self-sustenance might be on the horizon.

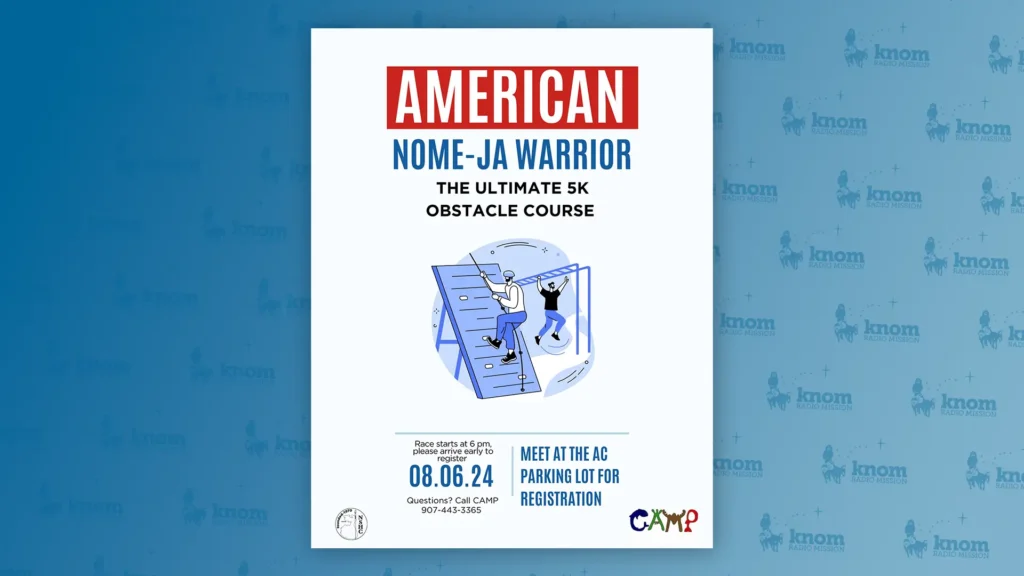

Image at top: Savoonga’s chief reindeer herder, Richmond Toolie, at the mobile reindeer processing plant (Photo: Gabe Colombo, KNOM, July 2018).