Nome, Alaska– A handful of apps are making it easier for rural communities to report on climate change in Alaska. With a swipe of a smartphone, locals can submit environmental observations, and there’s even an app aimed at preventing further change.

Mike Sloan pulls his smartphone out of his pocket. It takes a few seconds, but finally, the LEO Reporter app appears on his screen.

“Slow internet…” Sloan explains.

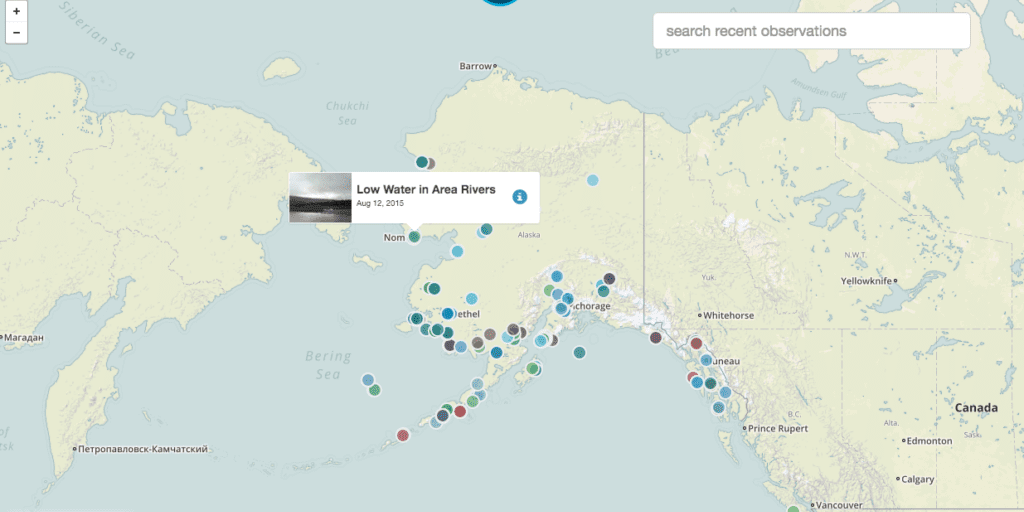

The screen on his smartphone shows the state of Alaska speckled with different colored dots, each representing a different observation.

Because we’re in Nome, it automatically zooms in to an aerial view of town. Sloan taps on a little light blue dot just off the coast. It’s a post from January 1, 2013.

“Actually, it was a post I did,” Sloan admits.

Sloan is the Director of Tribal Resources for Nome Eskimo Community. He’s also a Local Environmental Observer, or LEO.

The Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium created the LEO Network back in 2012 as a way for locals to document unusual environmental events like coastal erosion, wildfires, or even stranded snowmachiners.

“We had a strong winter wind that broke off the sea ice in front of Nome and moved it off shore [and] there was a snowmachiner trapped on the ice floe,” Sloan explains, adding “they were able to save him.”

After Sloan submitted his observation to the LEO Network, it was then tagged with a similar event in the Canadian Arctic. Sloan says the LEO Reporter app makes it easy for anyone to connect the dots, more specifically across Alaska.

“Say, if we have bird die-offs in Kodiak, we can go to LEO, look for bird observations, and it will pull up any other bird observations around the state.”

Five-hundred miles southwest of Nome, residents of St. Paul Island in the Pribilofs are using a similar app. It’s called the Bering Watch Citizen Sentinel App. Pamela Lestenkof co-directs the Ecosystem Conservation Office on St. Paul Island.

“Back in St. Paul, it’s our hunters, our beachcombers, and our fishers,” Lestenkof explains, “they’re the ones that are out there on the land, so they’re the first [that would] see a stranded marine mammal or dead birds.”

Locals have been sharing observations on Facebook for years, so Lestenkof says a database of those observations just made sense.

“And then once it’s uploaded in our database, we can publish it to Facebook,” Lestenkof says, “so there’s incentive for them to share it.”

But not all apps are aimed at observing changes. Gino Graziano helped develop one aimed at preventing them.

“Let’s see here… where did I put it?” Graziano says as he swipes through his smartphone. “There it is. It’s Alaska Weeds ID.”

Graziano teaches classes on invasive species at UAF’s Cooperative Extension Service in Fairbanks. He and his colleagues teamed up with the US Fish and Wildlife Service and the University of Georgia to develop the Alaska Weeds ID app that helps people identify weeds native to their area and report nonnative or invasive ones.

The app takes you through a series of descriptors, like leaf shape and leaf arrangement.

“And then, it will ask if the leaves are smooth or do they have little teeth or spines on them or hairs,” Graziano says.

Finally, it asks about flower color and flower arrangement.

“And you end up with what type of species it is. So, we end up with a couple of different options and we can pick bird vetch from that,” Graziano says as an example.

If you do come across an invasive plant like bird vetch, which has invaded Alaska’s interior, you can send in a report with a photo, description and location directly from your phone.

“And then a message actually goes to me,” Graziano admits.

If the plant is a serious threat and on public property, Graziano would contact a local land manager to remove it. Western Alaska is still largely free of invasive species, and Graziano hopes this app helps keep it that way.

“That’s really the key to invasive species management—is getting on it early,” says Graziano.

Ultimately, that’s what all these apps are hoping to do. Climate change is already affecting western Alaska, but locals can now help document those changes and, with the help of their smartphones, be more aware of what’s to come.