This coming fall, the Nome Elementary School (NES) will debut Nome’s first Iñupiaq immersion program in an ongoing effort to revitalize one of many Alaska Native languages.

KNOM’s JoJo Phillips has more from the program’s certified instructor.

As the longer days of summer-break beckon, Western Alaskan students and teachers alike are ready to leave their classrooms behind and head outside. But for Kiminaq Maddy Alvanna-Stimpfle, a second-grade teacher with the Nome Elementary School, there is plenty of work left to do.

“I’ve been busy with schoolwork and getting things ready for next year.”

Starting in the fall, Alvanna-Stimpfle will be the first certified instructor of a new Iñupiaq immersion school for kindergartners in Nome. Opening up an immersion classroom has been an ambition of hers for a long time.

“When I was an eight-year-old I got to travel to New Zealand and I got to visit their Maori language immersion schools. As an eight-year-old I had an immediate thought that this is what I want to do. I want to be able to speak to my cousins and classmates in Nome (in Inupiaq) and that was my dream as an eight-year-old.”

Last November, Nome educators were able to visit the Ayaprun Elitnaurvik immersion school in Bethel. Alvanna-Stimpfle, who was among the visitors, remarked on how quickly students were picking up their native language.

“By the third month, all the kindergarteners there completely understood their teachers speaking to them only in Yup’ik.”

In Nome, the upcoming kindergarten immersion program will focus first on language comprehension. Speaking Inupiaq comes later in second or third grade, according to Alvanna-Stimpfle.

Building a successful program from the ground up is a daunting task. Alvanna-Stimpfle along with Iviilik Hattie Keller, and other Nome educators, have been fundraising and planning for years. In regard to the many obstacles her and others have overcome, Alvanna-Stimpfle refers to the Wayne Gretzky school of facing challenges head-on:

“The way that I’ve been thinking about it lately is it’s kind of similar to a basketball game. You can’t make a game-winning shot if you don’t shoot the ball. This is us attempting to shoot the ball.”

She also recognizes that parents will have to decide whether or not to enroll their children into the classroom. In order to limit any future child-parent language barrier, Alvanna-Stimpfle is coordinating with the University of Alaska Northwest Campus in Nome to offer an Inupiaq class for parents whose children have enrolled in the school.

That’s just one example of community support the program has garnered from local entities. Keller has successfully procured grants from Sitnasuak Native Corporation, Bering Straits Native Corporation, Norton Sound Health Care Corporation, King Island Native Community, Kawerak, and Wells Fargo.

In Alvanna-Stimpfle’s view, the benefits of the immersion program far outweigh any risks. In a follow-up email to KNOM, she noted students in language immersion programs have higher graduations rates, higher test scores, in addition to lower rates of domestic violence, homicide, and suicide.

In her words, “the immersion experience can positively benefit our community because it will promote the strength, health and well being of our children. Learning your own language strengths ones identity. Knowing who you are builds up a person’s confidence… Providing our children with an opportunity to learn Inupiaq will positively impact our community by raising children who are grounded in who they are: Inupiat.”

Across Alaska and around the world, immersion classrooms have become a leading tool in revitalizing indigenous languages. Studies show many Alaska Native languages are in danger of going extinct. Programs such as Nome’s are integral to a larger statewide movement for Alaska Native Language Revitalization.

Qiġñaaq Cordelia Kellie sits on the board of Kipiġniuqtit Iñupiuraallanikun, a coalition collecting information about Inupiaq speakers in Western Alaska. According to Kellie, there’s an established theory regarding how long it takes for a culture to revitalize their language.

“Something that’s been said in language communities is that it takes three generations to revitalize the language, which is the most exciting thing because our Elders have been doing this work with the bilingual program.”

Kellie sees early-learning immersion programs as the final step for language revitalization.

“This generation—with all the grassroots organizing that’s happening—is going to help the next generation, which we hope is when we really [get to] see these immersion schools that are active and producing speakers. That would be the three generations to complete the cycle of bringing back the Inupiaq language.”

In Nome, Alvanna-Stimpfle is excited to get going on the program in the fall. She has a message to her future students, “Ilisazaqta Inupiaqtun—let’s learn in Inupiaq,” said Alvanna-Stimpfle.

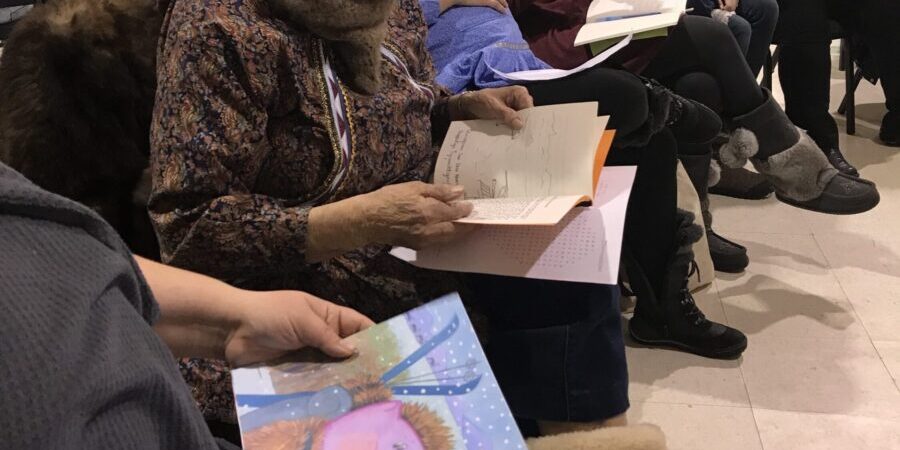

Image at top: During the 2019 Inupiat Summit in Kotzebue, participants looked at Iñupiaq-learning books shared by Raymond Ipalook. Photo from Katie Kazmierski, KNOM (2019).