A sonar system aboard the Coast Guard icebreaker Healy lit up in mid October as the vessel zig-zagged across the Chukchi Sea. It was near the end of the Healy’s two-week deployment. Two officers with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration leaned toward a wall of computer monitors glowing with survey lines.

“On that line, what occurred is something that we call a blowout, usually due to bad weather, you can have a interruption in that data," NOAA's Pacific Hydrographic Branch Chief, James Miller, explained.

“So this was a bit puzzling, because the weather was nice. So they talked to the ship's command and said, ‘Hey, I know this was our last line, but if it's possible if we could turn around and just collect one more swath of coverage, get one more survey line over this object on the seabed.’ And they did,” Miller said.

The officers, Taylor Krabiel and Lucas Doran, began sending the data to their colleagues to make sense of the anomaly.

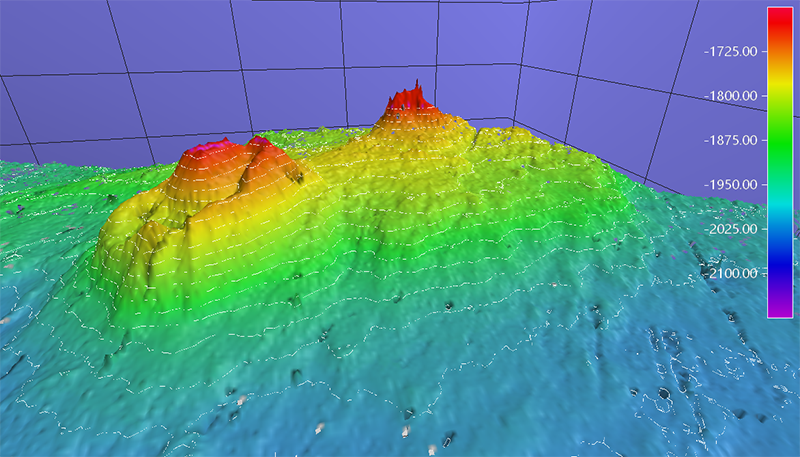

The discovery revealed an underwater, 1,600-foot-tall volcano-like feature protruding from the sea floor. For context, that’s about the size of three Washington Monuments stacked one on top of the other. The team also discovered a gas plume rising from the feature, meaning what they found was especially rare.

“There was excitement initially, but then that excitement only grew as they reached out to scientists that suggested that it's a potentially very significant feature of its kind,” Miller said.

Miller said that beyond the intriguing research opportunities the feature presents, it could also be the largest so-called “mud volcano” ever discovered.

"Comparable features of that type exist in the Mackenzie Delta and other regions of the world. But this one is considerably larger than comparable ones,” Miller said.

Against all odds

The team's journey to the Arctic, a first for many of the early-career scientists on the mission, almost didn’t happen.

The crew originally planned on carrying out its Arctic Port Access Route Study mission aboard NOAA’s Fairweather research vessel. According to NOAA Navigation Manager Lieutenant Caroline Wilkinson, that ship ran into mechanical issues in the spring.

“We thought that, unfortunately, that might be the end of our hopes to complete the survey for this 2024 field season, we kind of were starting to internally make some plans to conduct this in 2025,” Wilkinson said.

The Healy also ran into mechanical issues of its own this summer, prompting the cancellation of two other scheduled scientific missions. But the Coast Guard surprisingly opened up proposals for new missions through the National Science Foundation after the Healy’s repairs were completed.

The catch? Applicants had just two weeks to submit before being whisked away to the Arctic.

“We had a project that was 75% there, planned for the Fairweather, and so with the hard work of our personnel we were able to have a number of internal meetings in order to get that plan to 100%,” Wilkinson said.

The researchers also said that the Healy carried an advanced multibeam sonar system, capable of reaching depths the Fairweather could not. If it weren’t for the Healy, they might not have found the feature at all.

The research possibilities presented by the feature are already causing NOAA to reimagine its plans for next year. The agency hopes to send unmanned drones to investigate the feature further, in addition to completing a study for a new corridor between Utqiagvik and the Canadian border.