Iditarod mushers racing their dogs to Nome this year are doing it with a smaller team on the gangline. The race reduced the maximum team size from 16 to 14.

Ben Matheson has more on what this means for race strategies, speeds, and the tradeoffs that mushers face as they travel across Alaska.

24 hours before the race began, defending Iditarod champion Joar Liefseth Ulsom was facing a tough decision on which dogs to bring to the starting chute.

“Have you chosen your 14?”

“No, I haven’t.”

This year, competitive mushers like Leifseth Ulsom had to be extra choosey in building their lineup.

“I really thought 16 dogs was one of the things that made this race unique and special, one of things. I, personally, would like to run 16 dogs. We’ll see how it goes this year. Maybe I’ll like it; we’ll see.”

Over the course of a race, there are eight fewer booties to change, less food to pack, and eight fewer paws that need ointment. And that’s one of the main reasons why the Iditarod Board changed the rule: because of the potential for enhanced dog care. But more dogs mean more pulling and climbing power for mushers looking to move quickly across the country.

Nenana musher Aaron Burmeister says he has mixed emotions. He likes racing 16 dogs and even the 20-dog teams that were allowed when he first started racing.

“Do we need that dog power? No? In today’s Iditarod, with the nutrition, the training, the evolution of the sled dogs, you really don’t need more than 12. They’re incredible, powerful athletes.”

The Iditarod joins other top races in restricting mushers to smaller teams. The 1,000-mile Yukon Quest only allows 14 dogs, and a few years ago, Kuskokwim 300 dropped from 14 to 12 dogs. Four-time winner Martin Buser doesn’t like the new rule, saying it puts heavier mushers at a slight disadvantage.

“I want to maintain an open mind. Maybe we’re selecting if 16 or 20 you can take a dog that could be left behind. I don’t mind going one year with 14 dogs, even though we know it’s not because of strategy or race statistics. It’s simply done for money savings for the race committee, and that’s why I don’t agree with it.”

Buser is referring to the hundreds of dogs dropped each year in remote checkpoints. Veterinarians and volunteers in checkpoints watch over the dogs before the Iditarod Air Force flies them back to Anchorage.

Mushers have never been required to start with 16 dogs, and some teams chose in the past to start with a smaller string. But more dogs means more options. Mushers can bring a young dog that will gain valuable racing experience, but doesn’t need to make the full trip to Nome. And in recent years, some mushers have experimented with carrying a few dogs in the sled bag or in a trailer to both modulate speed and bank extra rest. A smaller team complicates the developing strategy.

2017 winner Mitch Seavey would prefer to stick with 16.

“I predict mushers (will be) more reluctant to return dogs from the trail. I think they’re going to want to keep them as long as possible. Personally, I would rather see it at 16. It’s a diminished race. I think it’s a little more stress and pressure placed on fewer dogs. We’ve shown we can handle 16 year after year; that’s really not a problem.”

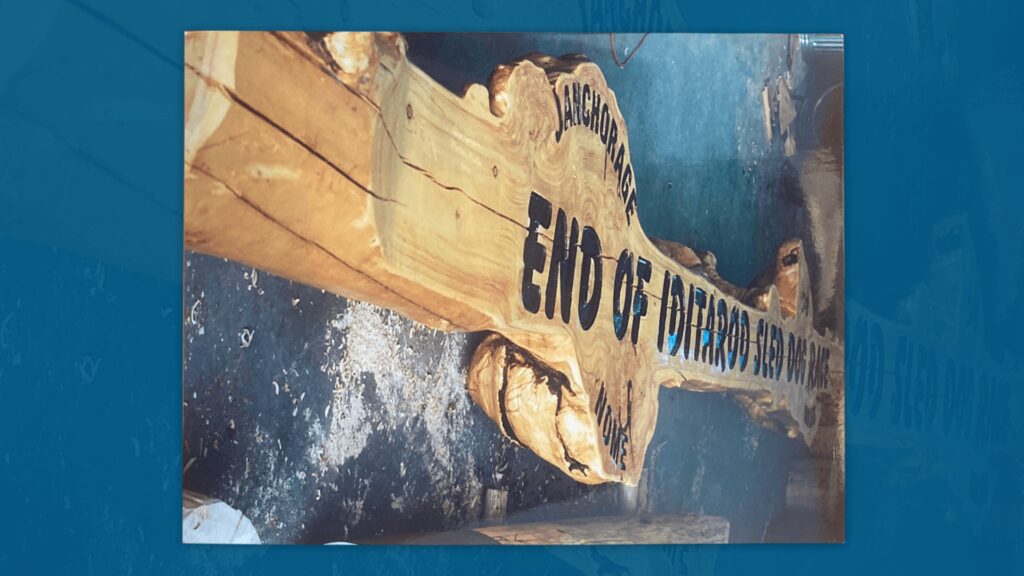

Once the race is down to the last few days, mushers typically drop their slower dogs and sometimes finish with small teams. When they pass beneath the Burled Arch, they can finish with as few as five.

Image at top: five Iditarod 2019 teams headed toward the Yentna Station checkpoint. Photo: Zachariah Hughes, Alaska Public Media.