As Nome stands on the precipice of significant economic transformation, with plans for a massive port expansion already underway, the community is faced with another pivotal decision— whether or not to embrace nuclear microreactors as a part of its future energy strategy. While these projects promise economic growth and opportunities, they also bring challenges and choices about the kind of future Nome wants to build.

Michael Valore, Senior Director for Advanced Reactor Commercialization at Westinghouse Electric Company, and Gwen Holdmann, Founding Director of the Alaska Center for Energy and Power, discussed the microreactor technology’s energy potential and environmental concerns during a live radio interview with KNOM.

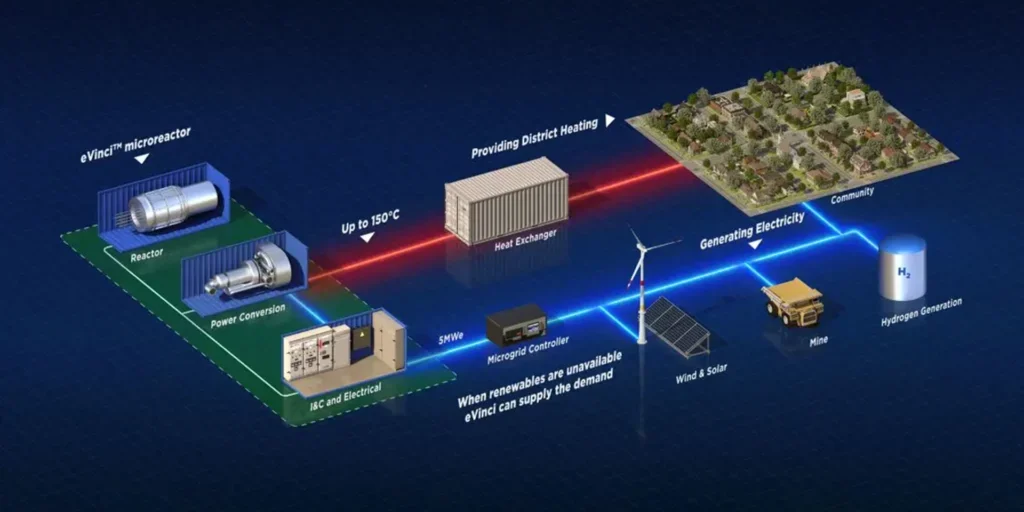

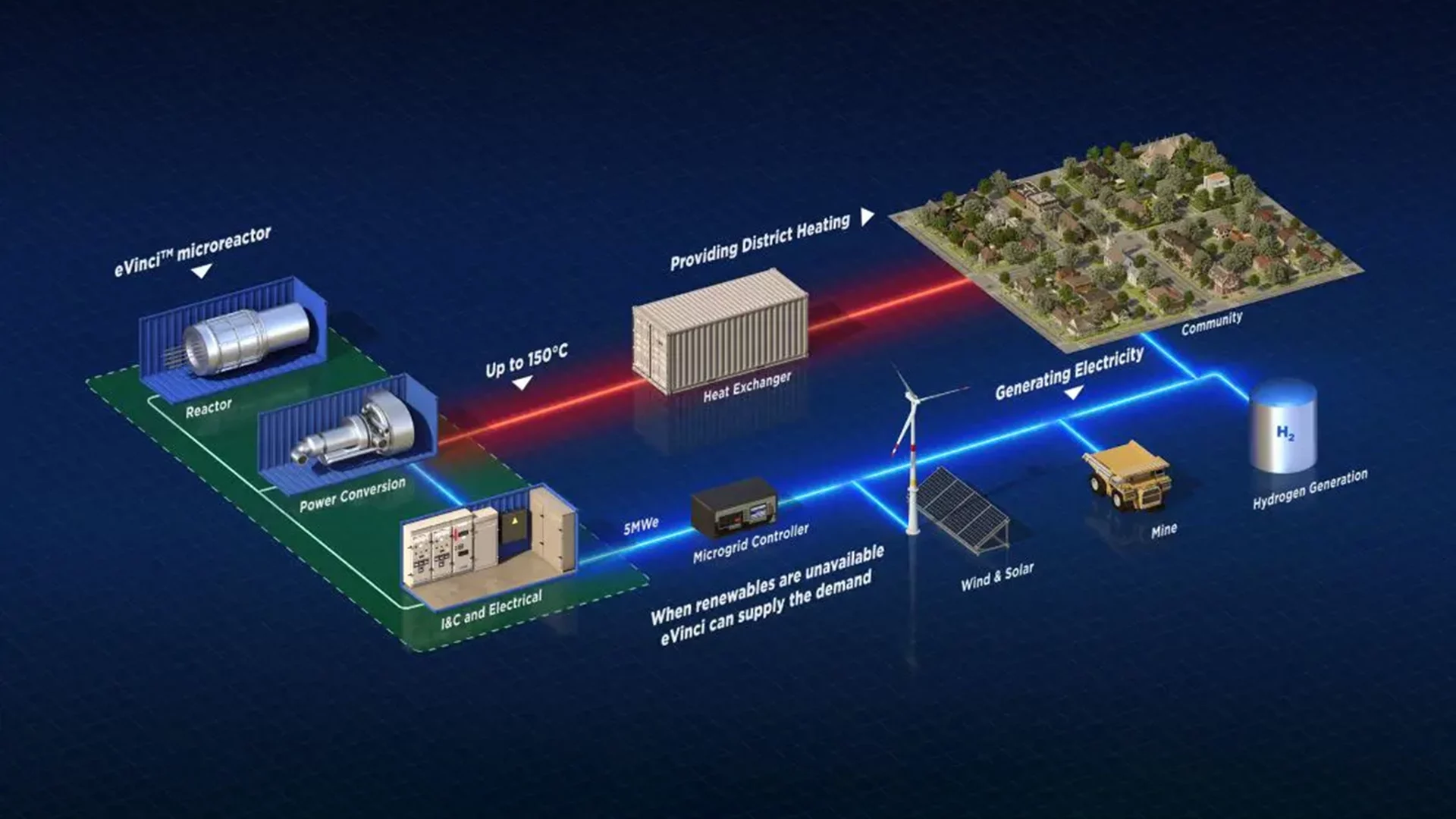

Unlike traditional nuclear reactors that are designed to power large cities with outputs ranging from 500 to 1,000 megawatts, microreactors like Westinghouse’s new eVinci system operate on a much smaller scale. Microreactors are about the size of a small building, producing anywhere from a few megawatts up to 20 megawatts. This makes them a suitable option for communities like Nome, where peak demand currently hovers around five megawatts.

These compact units are designed to be significantly safer and more adaptable than their larger counterparts. The eVinci system, described by Valore as a “nuclear battery,” does not use water for cooling, reducing the complexity and enhancing safety. It utilizes heat pipes for transferring nuclear-generated heat into electricity through a process known as the Brayton cycle, akin to the operation of a jet engine.

One of the distinguishing features of the eVinci system is its use of TRISO fuel. This advanced fuel type encapsulates uranium pellets within a durable ceramic-like layer, ensuring the reactor remains safe even under extreme conditions.

“Think of it like a ceramic that encapsulates every one of these tiny pebbles. The safety aspect is that even if you can’t control your reaction any longer, so your systems all fail, which is an extraordinarily unlikely event, the actual kernel or uranium will not exceed the temperature that it would take to break or melt that kind of ceramic outer coating.” Valore said. “The US DOE (Department of Energy) has even stated it’s the most robust fuel form on Earth, and we believe that as well.”

Addressing the community’s concerns about safety, Valore reassured that nuclear energy is among the safest forms of power generation, backed by stringent regulations and oversight from the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission. Furthermore, the design’s passive cooling systems that feature very few moving parts enhances its safety profile, making it nearly impossible for the reactor to experience a meltdown.

The economic benefits of microreactors may be significant, especially in regions like Western Alaska, where energy costs can fluctuate greatly due to a reliance on diesel. According to Valore, the eVinci system could offer a cost-effective alternative, potentially reducing energy expenses by 10 to 40 percent compared to diesel. Additionally, its capacity to provide both electricity as well as heating via a district heating setup could further enhance its economic viability.

“The idea of potentially replacing diesel fuel in our communities with these sorts of small thermal batteries is really exciting to me because I think it could really benefit communities in the region in terms of both power and heat, and really insulate us more from these different fuel prices, which is just this continual roller coaster for many of the communities in our region.” Holdmann said.

Holdmann highlighted the environmental advantages of transitioning to microreactors. In remote and cold regions like Nome, where soil and water contamination from diesel spills are common concerns, microreactors present a potentially cleaner, more stable energy source.

“There’s a lot of contamination of soil and water here in Alaska from diesel fuel spills in our communities. I’ve spent a lot of time out in rural communities in this region, and there’s very few that haven’t had some sort of fuel spill or some sort of contamination.” Holdmann said, noting that compared to older nuclear reactor designs, for microreactors, “the vectors for environmental contamination are really, really different than for conventional legacy reactors, they can’t melt down, they’re basically not capable of melting down because of these passive cooling features.”

The eVinci microreactor is still in development at Westinghouse and according to Valore, they plan to have their first unit operational sometime in 2026. A microreactor in Nome, if approved, would not be installed until the end of the decade at the earliest. Regarding cost, it is too early to say exactly what such a system would cost to the city and taxpayer as funding via the federal government in the form of tax credits or grants may be available in the future.

Valore and Holdmann will join the Nome Joint Utility System Wednesday, April 17 for a public discussion at Old St Joes from 2-4 and 6-8 p.m. to provide further details and answer questions from the public.