The Alaska Native Collaborative Hub for Research on Resilience and the Statewide Suicide Prevention Council partnered this month to host a webinar on suicide prevention among Alaska Native youth.

The webinar presented two different efforts to reduce suicide in Alaskan Native young people. The Quasgiq Model and Scammon Bay’s cultural activities both take a grassroots approach to prevention. They stressed the importance of preventative measures and supportive measures that already exist in youth’s lives. Both projects emphasized suicide prevention through positivity over suicide identification and intervention.

For the first project, Stacy Rasmus, Jim Allen, and Lisa Wexler presented their research. Known as the Quasgiq model, their work examines the process rural Alaskan villages undertake to prevent suicide. The process involves the whole village coming together, led by the Elders, in order to uplift the youth and help them cultivate a desire to live.

“The goal, as one Elder from Alakanuk said isn’t just, we don’t just want our young people to die. We want them to want to live and to feel loved,” Rasmus said.

The beauty of the Quasgiq model is that it distributes the responsibility of suicide prevention around the entire village, Rasmus said. Multiple individuals, from all facets of a young person’s life, have the power to step in and help a youth at risk. Everyone contributes to the atmosphere of positivity so that the youth feel wanted on every level.

In a similar tone of positivity, Georgianna Ningeulook, the lead prevention coordinator of Scammon Bay, talked about some home-grown initiatives she undertakes to help the young people of her village feel good about themselves. She would pick kids of her community up and give them opportunities to participate in activities important to Alaska native culture, Ningeulook said.

Through activities such as hunting and making traditional tools, Ningeulook tries to instill a sense of identity and belonging into youth who might otherwise feel lost. She said her activities teach the importance of “first, knowing yourself” and finding happiness in that identity.

“It’s important to know who you are. It helps so much in life. Because being Yup’ik means a lot of things and that also comes with the teachings that were given to us by our Elders, our parents,” Ningeulook said.

By educating Yup’ik youth about their tradition, Ningeulook’s programs teaches children to take joy in who they are.

Ningeulook dwelt fondly on many memories: the joy a young boy took in accomplishing his first catch after doubting that he could do it, the number of kids willing to help chop wood for their Elders throughout the summer. The joy in her voice was palpable.

The dual lifestyle of Yup’ik youth, the commitment to both the traditional subsistence lifestyle and the modern lifestyle of education and careers, can be difficult for some youth, Ningeulook.

“I really do believe that the kids struggle with this because I do. When I first left Scammon Bay, it was hard for me because I wanted to be home, but I knew I had to get a degree,” Ningeulook said.

Ningeulook described her programs as a natural take on prevention. She encourages youth to engage in activities that are already a part of their lifestyle and their cultural identity. By helping the young people find joy in these activities and by demonstrating to them that they have a support community all around them, Ningeulook hopes to offset any feelings of loneliness and hardship the children may experience.

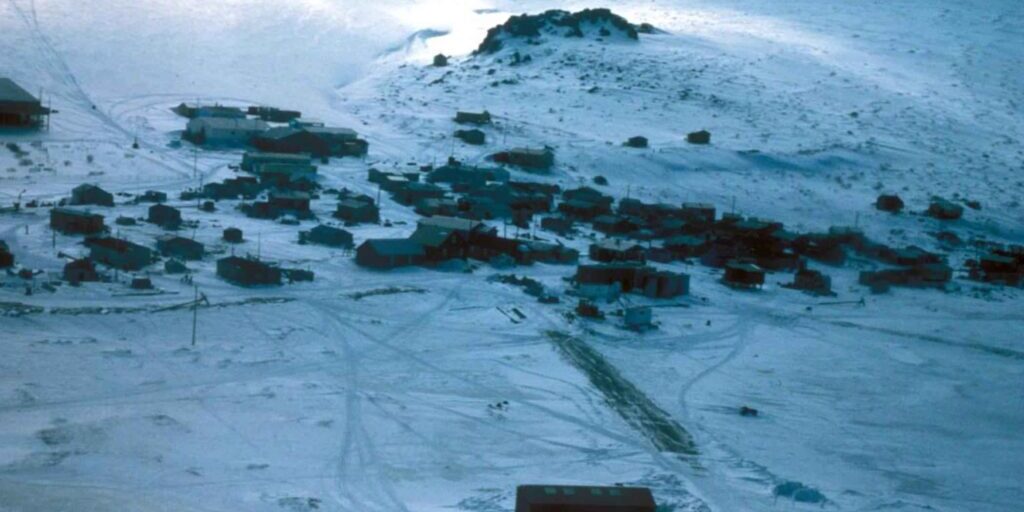

Image: Aerial view of Scammon Bay. Photo Courtesy of Fish and Wildlife Service, 1986.