One hundred and fourteen sexual assault kits have been tested and returned to Nome Police Department through the Alaska Crime Lab Capital Fund Project.

Many of the returned kits need some type of investigation, but right now NPD says they don’t have the experienced investigators required to do that. Those 114 kits don’t include current cases, but refer to previously untested, un-submitted kits. According to the Capital Project, their funding in this case is reserved for kits that had gone previously untested as of 2018.

Paul Kosto is the evidence custodian for the Nome Police. He explains that sexual assault kits can hold DNA for up to ten days before being administered.

“At times, a victim might have had sex with a consensual partner, and we are required to go back and get DNA samples from the consensual partner to eliminate them as a suspect in the case.”

The consensual partner’s DNA is identified through a process called DNA elimination testing. Out of the 114 kits sent back to NPD, 40 need additional DNA elimination testing.

Not only is that DNA potentially required for case resolution but also under the project, the DNA of non-suspects for that case must be removed from CODIS, the federal DNA database. The project’s timeline estimates a goal of 2021 to have all eligible profiles entered into the CODIS database.

Right now, NPD isn’t able to begin working on that elimination testing, Kosto says, for two reasons.

“We’re going to need a really experienced investigator. And we are also holding so that our, I think it’s a public liaison is now the title that it’s given, but it was the victims advocate position that Sharon Sparks was filling. We are getting her training so that we are able to go through this process and not re-victimize any victims.”

During a medical exam, nurses will typically ask the survivor questions about their consensual partners, and those answers are included in a medical exam report. That report is then given to the police, included in the related criminal case, and could assist with DNA elimination testing. But Kosto says in his experience, many NPD officers weren’t reading that medical report for additional information.

“The officers and the investigators have absolutely got to open that envelope and read that report because there may very well be revelations that they did not get on their initial interviews.”

Kosto says the department is trying to make this a teaching moment; an inexperienced officer may not realize that a survivor might be more comfortable sharing information with a nurse rather than an officer.

Some of the 114 kits go all the way back to 2005, so now an investigator may have to open up deep, years-old wounds during an investigation.

Beyond the kits needing DNA elimination testing, Kosto says there are kits with additional investigation required.

“Confirm on some of the cases if we are confident that a crime has been committed, so we have to review those cases. We have cases where there is some DNA evidence that exists but not enough information in the report so there needs to be some follow-up investigation on some of those cases. And then there’s a number of the cases where there’s just not enough DNA evidence to continue with the process using just DNA to investigate the crime.”

There is currently no timeline for NPD to complete additional investigation on the 114 returned kits. Kosto wrote to KNOM that approximately 60 of those cases could be eligible to be entered into the CODIS database.

Megan Peters, spokesperson for the Department of Public Safety, confirmed that Nome’s sexual assault kits are the first in the state to be returned under the Capital Project. Those were sent out in June of 2018, and over a year later, Kosto confirmed they were returned to NPD in mid-July of 2019.

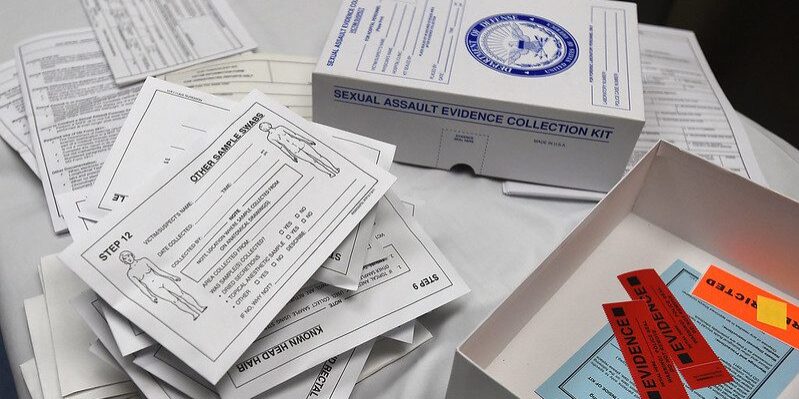

Image at top: A sexual assault evidence collection kit. Photo available on public domain via Flickr (2014).