Weather along the Iditarod Trail has been abnormal this year, with warm, wet conditions hitting mushers along much of the route.

It’s a consequence of an exceptionally bad winter along the Bering Sea coast, as Alaska Public Media’s Zachariah Hughes reports.

Kristy Berington is having boot trouble.

“We had rain, (of) which I’m not a fan: my stuff is constantly wet, (and) I can’t dry anything out. Including my feet.”

The trail has been wet, with occasional rain and sticky snow that’s slowed down her sled. The worst section so far was along the Yukon, heading north to Kaltag.

“It was, like, immediately after Eagle Island — it was bad. Like I said, 30 miles of just rough (trail). I’ve never seen water like that on the Yukon.”

It’s hardly just the Yukon that’s less frozen than usual. Upriver from Unalakleet, long leads of open water run parallel to sections of the trail, and there’s overflow.

“I’ve never seen it like that.”

Wade Marrs is changing socks and lacing up his mukluks in the Unalakleet checkpoint after a nap. He, too, is having trouble keeping things dry. But that’s sort of the least of his problems. Abysmal snow cover, abundant tussocks, and aggressive moguls cracked apart his sled on the way into the Iditarod checkpoint.

“One of the runners snapped on some moguls, and then the snapped piece hooked on a tussock and snapped the whole seat part of my sled right off the back.”

Parked on a slough in Unalakleet, Marrs’ sled runners are different lengths: one is missing about three feet, and he’s just had to cope with the damage for a few hundred miles.

One of the more dramatic effects of the warm winter is still to come further up the trail. Norton Sound doesn’t have any sea ice. Usually, in March, the ice is reaching its thickest extent. But from the beach in Unalakleet, the full horizon is blue ocean water, punctuated infrequently by lone icebergs. Typically, in winter, the shore is silent, save the slight tinkling of ice shifting.

This year, you can hear waves.

The last few Iditarods have seen diminished sea-ice conditions along the coast: one of the impacts of a rapidly warming Arctic. This year, freeze-up was late. Rough, warm weather has kept the sea ice from forming properly. And in February, a storm flooded areas around town.

“The slough, the high water came up above normal….it’s gonna be a tough spring.”

Mitty Johnson is a retired musher and helps run the Unalakleet checkpoint. This is the most open water he remembers ever seeing during Iditarod time.

“We’ve had it go out before… (but) you haven’t seen that in a long time.”

The other novelty this year is so much open water along sections of the river.

Reroutes and damp feet during a sled-dog race are an inconvenience, but the consequences for people that live along the Bering Sea coast are far more dire. Johnson says it makes travel along the rivers significantly more dangerous, when travelers break through the ice. Economically, the commercial fishing season for red king crab had to be shut down because there’s no ice through which to sink pots.

“No winter crabbing.”

Beyond commercial harvests, sea ice is crucial for subsistence hunting marine mammals in the spring for communities up and down the Bering Sea and Arctic coasts. Stormy weather in Nome this year has left huge piles of snow, but hardly any sea ice. On Sunday, what ice there was snapped off and floated out to sea, leaving open water to greet the mushers as they come in.

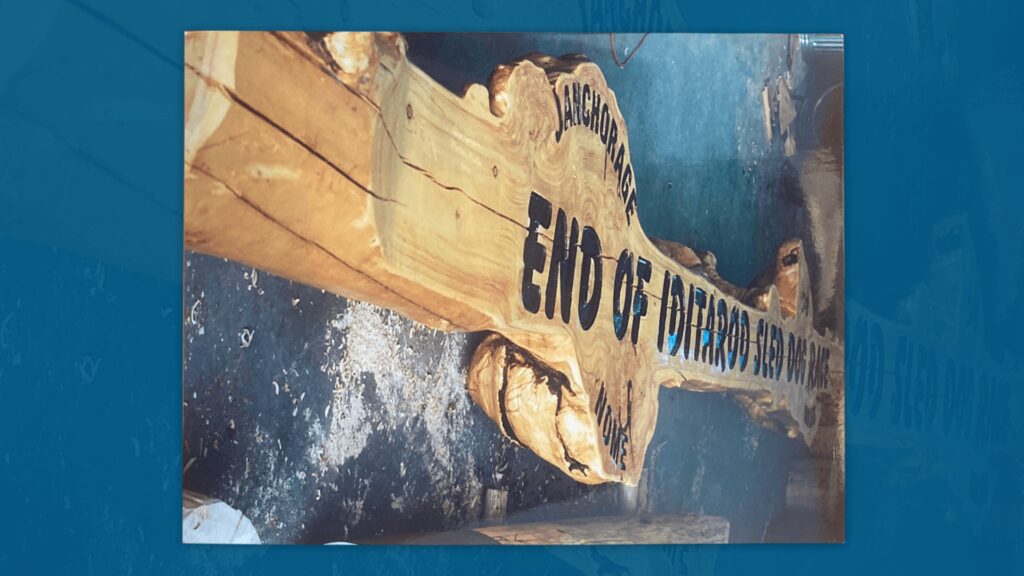

Image at top: An aerial view of Unalakleet during winter, with open water along the coast.