A resonating thud is the sound of Native Youth Olympics competitor Summer Sagoonick successfully kicking a ball suspended more than fifty inches above the gymnasium floor – with both feet.

Around Sagoonick, there is a bustle of activity. Hand-painted signs posted on the walls at the Anthony A. Andrews School in St. Michael, Alaska, exclaim warm greetings like “Good Luck Gambell” and “Go Shaktoolik Wolverines.” Just outside the gym doors, the “Storm Shack” offers nachos, slurpies, and other treats to hungry spectators. Directly across from the concession stand, a hot t-shirt press awaits anyone interested in purchasing NYO-themed, iron-on appliques. There’s a palpable energy at the school as elders, toddlers, parents, and other spectators weave in and out of the gym during the three-day event.

As Sagoonick strives to hit higher targets during the Two-foot High Kick, Unalakleet NYO Coach Nick Hanson is always close by.

While Sagoonick is a member of the Unalakleet Wolfpack, Hanson and other coaches frequently give guidance to competitors – whether they’re an Elim Eagle or a Savoonga Husky.

Hanson says that helping each other out is the spirit of NYO.

“Sportsmanship is key, because if you’re not out there helping each other get better, then no one is going to get better! [He laughs.] You know, we’re out here to teach, and be, you know, ambassadors of our community, and of our culture. Most of all, you want to get out there and have fun and help teach others. Whatever you know, if there’s someone who’s struggling, you know, help them out.”

Some days during training, Hanson even lets the kids run the show.

“I kind of just stand back some days and just let them do it. I’ll work out with them and practice with them, and I’ll just watch them coach each other. And I think they learn more from being coaches, you know, that’s just the way that we roll.”

When Hanson isn’t coaching NYO, he’s competing himself. He’s a regular on the broadcasted sports competition “American Ninja Warrior,” which Hanson says is the only other situation in which he’s experienced the same sense of camaraderie.

“There’s no games like this. That camaraderie, that everybody-wants-everybody-to-do-their-best-type vibe that it has, [American Ninja Warrior & NYO] are the only two places that I’ve ever had it. And NYO is where it started.”

This display of sportsmanship among young athletes is one of many draws that brings Paul “Bebucks” Ivanoff to the games this year.

“My daughter is competing, but you know, we’re here to support all the kids, and the Unalakleet Wolfpack. And it’s just great to see these amazing athletes perform. This is unlike any sport that you’ll watch, where coaches and athletes encourage each other to do their best – whether it’s for first place or otherwise. It’s really encouraging to see all the kids perform, and do their best.”

With a competition that prioritizes community, it’s not surprising to see former competitors return in new roles. In 2013, sixteen-year old Apaay Campbell of Gambell shattered a twenty-year-old world record for the Kneel Jump. Five years later, she returns to NYO as an assistant head official.

“After I graduated, I was asked to officiate. It’s so much fun. There’s some kind of vibe to this sport, and it feels much happier than other sports. It’s not so competitive and not so serious.”

With an already lengthy and decorated NYO career behind her, Campbell says she continues to participate as an official because she finds the role rewarding.

“I just love being here with everybody, all together, having fun. When you officiate, you kind of coach them on what to do, and when they finally kick it or when they finally jump their best, it’s the best feeling in the world.”

For NYO competitor Demi Levi, the opportunity to test her own physical limits is an exciting and unique opportunity compared to popular team sports like basketball.

“Basketball is judged on how well you do as a team, but in NYO, you’re judged on how far physically you can go for lots of challenging events.”

But for a sport that predominately features individual competitors – only the Wrist Carry requires the formation of a team – NYO certainly doesn’t lack team spirit. Competing in her hometown for this year’s tournament, Levi fondly remembers her community’s support during the games.

“Today, I felt like I was really supported by my community while I was doing the Eskimo Stick Pull and the Seal Hop. I heard lots of people calling out my name: ‘Go Demi! Keep Going! Keep on Going, Don’t Stop!’”

While the festive atmosphere of NYO is sustained through the gamesmanship of each athlete, coach, official, and spectator, a significant amount of work behind the scenes is required to make the games a reality. Linda Cooper can attest to that:

“I am the Activities Admin Assistant in the district office, but when we run events like this, I’m the Assistant Tournament Director, and I work under [Tournament Director] Jeff Erickson. I’m from Unalakleet, Alaska. I was raised there, graduated, so I’ve been around [these] BSSD activities for a while.”

Cooper and other members of the school district’s administration lay the groundwork to make the games a reality.

“I get to lay out the awards before the award ceremony. I do a lot of the background work: set up the hospitality room, make the orders, make the snacks, paperwork – a lot of paperwork.”

Due to her position, Cooper gets to interact with a lot of people – administrators and students alike. She says that the difference between NYO and other sports is clear.

“A lot of people are familiar with basketball, volleyball, and wrestling tournaments and the ways those work. NYO is kind of really expanded, and a lot of kids really enjoy this. If you go out and ask a lot of the kids around here: ‘What is your favorite sport?’ many of them say ‘NYO.’”

And if you ask Cooper what makes NYO a favorite in the region, she’ll get chills.

“NYO’s the best, because you’ve got this positive atmosphere, but it’s still as competitive as another event – I’m getting chills just thinking about it! You’re challenging yourself not only for yourself but for the team, whatever you can do. So, just the atmosphere is different. There’s not very many politics. It’s fun, it relates to the culture, and even for outsiders who haven’t seen this type of thing, it’s amazing for them to see kids who can kick a [basketball] rim!”

And these kids can certainly kick near a rim. This year’s competition saw Allie Ivanoff of Unalakleet break three district records, including kicking two inches lower than the state record for the One-foot High Kick. And at last weekend’s tournament, Arctic Ivanoff, also from Unalakleet, was the Boys’ Outstanding Athlete for the third year in a row.

But Unalakleet isn’t the only school that claims top performers. Competitors from Elim, Gambell, Savoonga, Shishmaref, Stebbins, St. Michael, and Teller all brought home first place medals. While each NYO competitor is encouraged to participate in every offered event, if you asked a NYO athlete if they were more of a “jumper” than a “reacher,” they would probably have an answer for you. The unique strengths of individuals across the Bering Strait region are displayed in the wide variety of top performers. And either way, all participating teams get a chance at recognition in a parade.

Encouragement of shared success in competition found in NYO shouldn’t be surprising, considering the games were started in 1971 to honor traditional values. Each display of physical prowess from the Alaskan High Kick to the Seal Hop tests and proves essential skills required in their ancestors’ lives. As the Cook Inlet Tribal Council explains, sharing information with and helping others out was a necessity for survival. And for the many students in the Bering Strait region who frequently participate in subsistence-based activities, these games can’t get any more relevant.

As the games concluded last Saturday afternoon, it seemed fitting for Coach Hanson to introduce “Scream & Run,” a traditional game from the Blackfoot Nation in Montana, as the tournament directors prepped for the award ceremony.

“One breath and as far as you can run. As soon as you run out of breath or go (intake of breath) to try to scream again, that’s all you get, you have to stop right there and that’s where you have to put your mark. And the reason why [the Blackfoot Nation] would play this game, is because back in the day when another tribe would come and try to take over their community, the kids would be out playing. And they would send the kid, who could scream and run the farthest, screaming and running back to the community to let the warriors know to get ready and fight. And that was the tradition behind this game, so it’s about taking care of your village.”

It’s about taking care of your village. That’s what the Native Youth Olympics are about.

The state-wide championships for NYO continue today and tomorrow at the Alaska Airlines Center in Anchorage, Alaska.

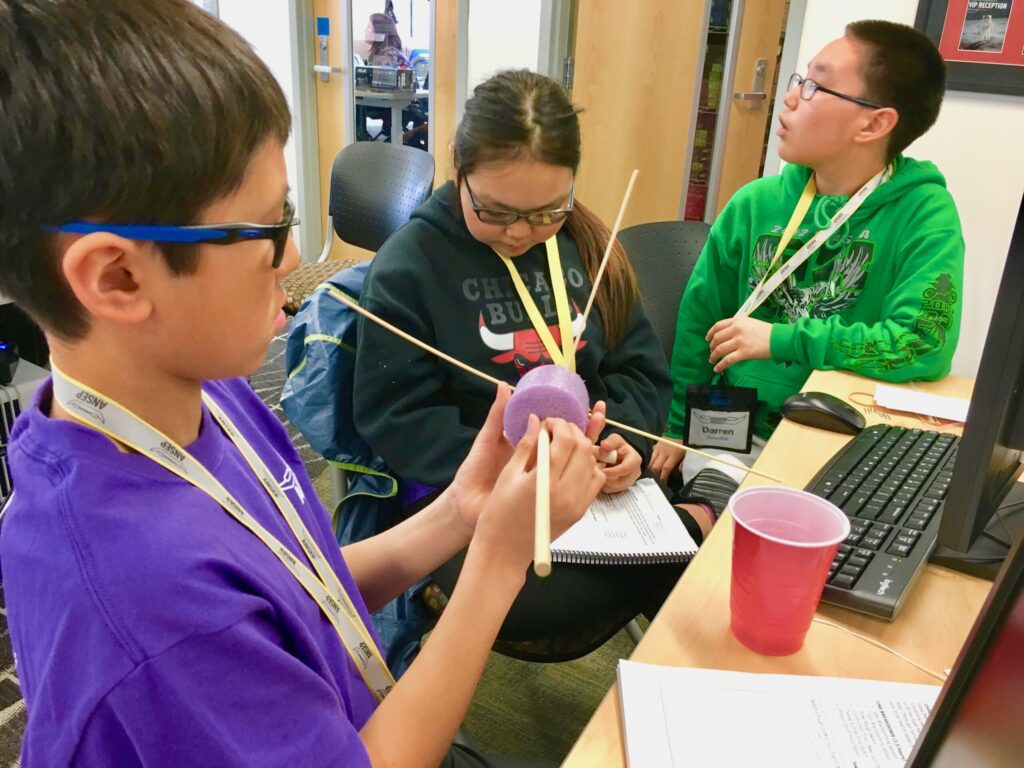

Image at top: Unalakleet competitors (left: Allie Ivanoff, right: Summer Sagoonick) lend each other a helping hand at the 33rd annual BSSD NYO tournament held in St. Michael in 2018. Photo: Karen Trop/KNOM.