A group of marine scientists is visiting Western Alaska this week to discuss the results of a second bottom-trawl survey of the northern Bering Sea.

The team is with NOAA’s Alaska Fisheries Science Center, based in Seattle. This round of research comes seven years after their first survey of the area in 2010.

“We were really quite surprised and quite shocked at what a big difference there was.”

That’s Bob Lauth. He’s a research fisheries scientist, and he leads the Bering Strait survey program. This summer, his team used a large trawl net to survey and identify species in the northern Bering Sea.

Among the results: the pollock population jumped by 6000 percent, and there were also large increases in Pacific cod and smaller snow crab. According to the surveys, the water is warmer than it was in 2010, so cold-water species like saffron cod were much sparser, with Arctic cod numbers down 90 percent.

There were also higher populations of jellyfish and sea stars, called “keystone species” because they help to structure marine ecosystems.

“In an area where you may have concerns about food supplies for marine mammals and walrus and whatnot, something like an increase in sea stars could be something we really want to track.”

That’s Lyle Britt, a fisheries research biologist on the team. He says the warmer water has caused a shift from a “bottom-up” ecosystem — centered around the sea floor — to a “top-down” one — with more activity higher up in the water.

“When you have two that are just so diametrically different, it’s really hard to say — is this a trend, or is this more like a weather event? We just don’t know now.”

Britt hits on a key footnote of the findings: The team needs more data to accurately describe what’s changing. Jeff Napp is director of the Resource Assessment and Conservation Engineering Division at NOAA. He says it’s about identifying larger processes within the ecosystem.

“Is the change that we saw last year really tied to the ice, or is it tied to something else? What things change first? What things change more slowly? It’s those mechanisms we really want to be able to discover, so that we can do a better job at predicting, and then communicate that along the way to the people living here, the people who are reliant on the resources.”

While they’re in Nome, the team is meeting with representatives at Kawerak, the Norton Sound Economic Development Corporation, and other regional organizations. They’re also teleconferencing with leaders from some of the Bering Strait communities that are most dependent on these marine ecosystems: places like Gambell, Savoonga, and Wales. And they plan to send their report to all the tribes in the region.

For now, the team says the increase in fish they saw this year doesn’t necessarily mean commercial fishing for pollock could start any time soon in the Bering Sea. Here’s Britt again:

“Given how mobile we know pollock can be, this could be an ephemeral thing: They’re here this year, and they’re not coming back. Or they’re here to stay. We just really don’t know. And even if, conceptually, say, this area was open to fishing, and there was interest, I think the time it would take even a company or something to even set up to do such a thing is going to be a number of years, and they’d want to know that these fish are truly going to be here for the long term before they’d even try.”

But if the funding is there, the scientists say, and they’re able to start doing surveys every other year, that answer could become much clearer as soon as 2019.

The entire report from the scientists’ surveys will available to the public online in the near future. Hard copies are available from Gay Sheffield, an Alaska SeaGrant Marine Advisory Program agent in Nome.

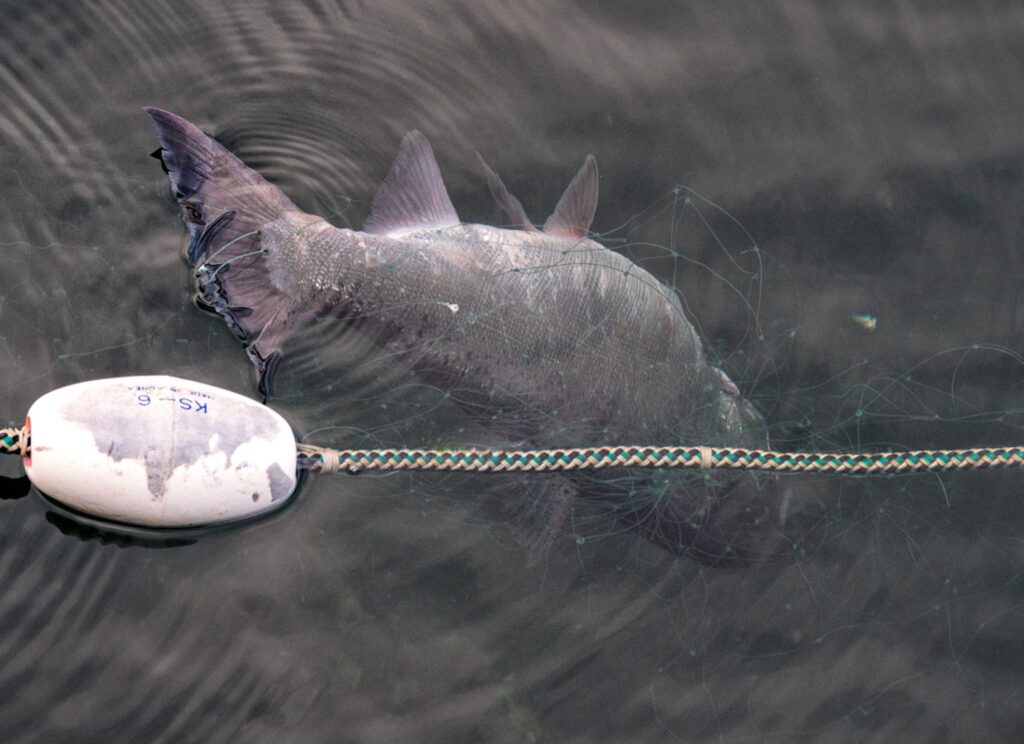

Image at top: Purple sea stars and other species caught during the Alaska Fisheries Science Center’s 2010 survey of the Northern Bering Sea (Photo: NOAA, used with permission)