Salmon are starting to run in rivers around the state, and also in Nome classrooms: on Wednesday a second-grade class at Nome Elementary wrapped up its months-long salmon incubation project.

“We received eggs around December 20, just before Christmas Break,” said John Mikulski, the Home School Coordinator charged with caring for the young silver salmon fry. “We got the eggs, so we started growing them. Then they become alevin, and then they turn into this as fry.”

Watching the salmon mature is part of the learning process, “from eggs to eyed eggs to alevin to fry,” one student said.

“When the kids come in, we talk about things,” Mikulski said. “We show them how to test the water. We have a test kit, and they run through the ph and things of that nature. So through the year, they learn different things about taking care of fish.”

The project’s goal is to observe in the classroom what is simultaneously happening in the students’ backyards, and throughout Alaska.

The salmon incubation program is sponsored by the 4-H club out of the University of Alaska. Second grade teacher Rita Smith has been running the program at the elementary school since 2005.

“We actually counted 77 fry that survived to the fry stage (out of 100 eggs),” she said. “Our largest fish measured out to be 53 mm. And Our heaviest fish turned out to be one gram. And that was pretty good.”

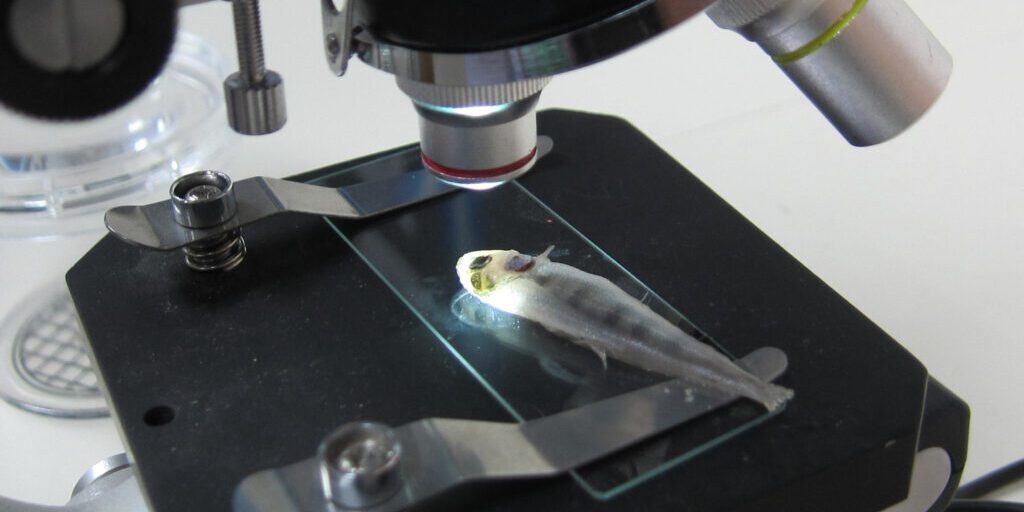

The students measured and weighed the fries and wrote observations in their notebooks. They also got a closer look at the eyeballs under a microscope.

“It’s like clear and white with black spots … kinda weird,” one said.

“It’s real black, and it has a little bit of hair,” another observed.

“It looks really slimy and awesome.”

“I bet it’s too small to eat.”

The lesson also looks at the salmon life cycle, from beginning to end—even when that end comes early.

“Clorox,” Mikulski said matter-of-factly. “That’s Clorox bleach. So what we do is put a mixture of Clorax bleach in the water, and you saw how quick that was. It’s almost instantaneous. So it’s the quickest way to do it.”

The quickest, but not how Mikulski wants to see the project end. The fish did not come from Nome rivers, and so the state Department of Fish and Game prohibits them from being released into the Nome waterways. That leaves Mikulski—and the class—with only one option.

“I’m not for it. I would have rather been able to release the fish,” he said. “I think it’s such a shame to euthanize that many fish. It’s not a whole lot, but still, they’re nice fish. And to do this, I’m totally against it. I grew them from eggs, so it’s just like my children, you know. “

Smith said she begins prepping her classroom students for the final stages of the project before the eggs even arrive. She hopes the final stage of the project teaches the students how delicate the salmon lifecycle is, and leads students to a greater interest in biology.