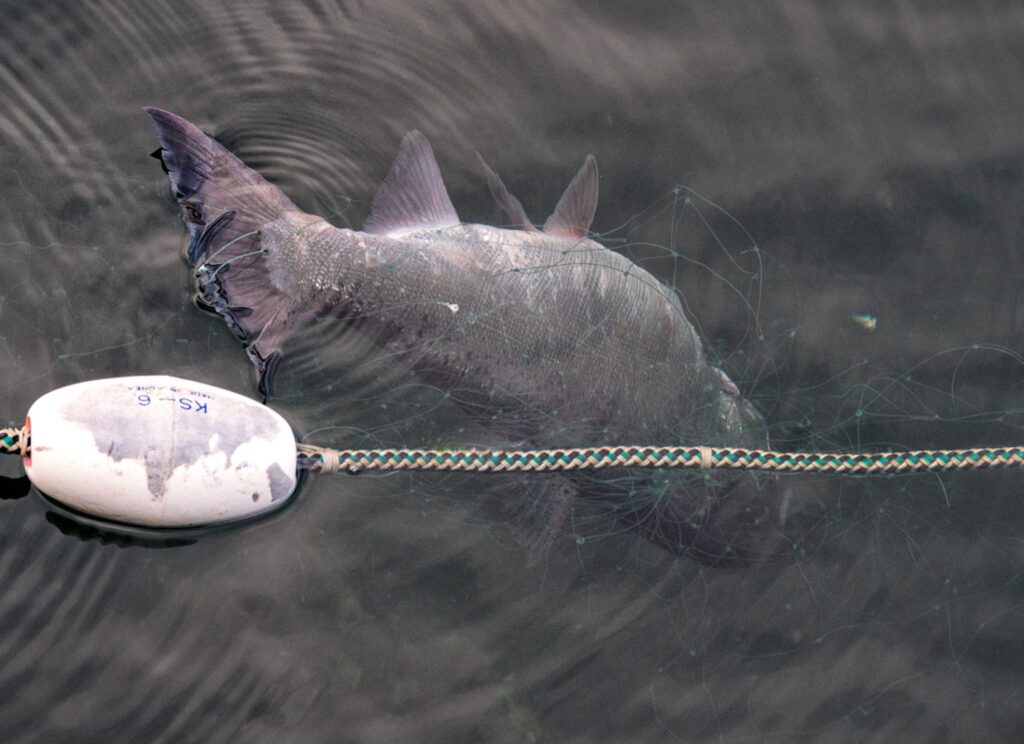

Salmon caught by pollock fisheries in the Bering Sea was among the most contentious issues before the North Pacific Fishery Management Council during its past week of meetings in Nome. On Saturday, after a day and a half of discussion and hours of public testimony, the council voted before a packed room to re-examine how it handles both Chinook and chum salmon bycatch.

The move potentially opens up the pollock fishing industry to new limitations and early closures, but fell far short of the immediate relief many subsistence users called for.

Those calls were delivered in person and directly to the Council, as dozens of local subsistence users spoke to the need for swift action.

Nome resident Barb Amarok spoke to the role salmon play in culture and identity: “Please hear what we have been saying about the importance of fish as a food staple to maintain our physical and spiritual well-being, and our identities as proud and distinct peoples. Salmon are not disposable. People are not disposable. So when the collateral damage of salmon bycatch threatens our existence, industry actions must be changed.”

Brandon Amahsuk spoke as a subsistence fisherman: “I have heard testimony from the pollock industry saying in the last couple of days they only catch a few salmon as bycatch. I ask you, in recent years, is 122,000 Chinook only a few? When the subsistence salmon fishermen aren’t even allowed to harvest one? [The industry is] being asked what to do. The subsistence user is being dictated to. Simply put, to not fish, to not put food on their table for their families.”

Louie Green Jr. echoed that sentiment: “We’re in a pathetic time of economics. I’m frustrated by what’s going on. Seeing as how the industry is allowed to take more and waste more than we are allowed to subsist on is very, a very hard thing for me to understand.”

John “Sky” Starkie spoke on behalf of the Association of Village Council Presidents and urged strong rollbacks of bycatch limits: “The inequities are just staggering for people on the river. And something needs to happen. I come before you to ask for a reduction of the performance standard to 14,500 which we believe is a very reasonable request. It represents the average bycatch taken over the last five or so years. If the industry can perform at that standard, they should be held to it, in this situation where every single fish counts.”

And Ben Stevens, a Koyukan Athabascan who traveled more than 480 miles from the Upper Yukon community of Stevens Village, numbering about 100 people, asked the Council for meaningful action: “You know, we’re just a bunch of normal folks [in Stevens Village] that really love life and appreciate love, kindness, each other, family. We’re not asking for anything but just a little consideration. But I am asking you, I am expecting you, I would like to demand of you, some courage to help us stem this tide.”

“Because it’s happening to us,” Stevens said, pounding the table with his fist. “The fact of the matter is the fish are going away, and we need help. You guys are it.”

Attempting to answers those calls to action, the Council unanimously voted for an analysis of salmon bycatch measures that they said puts pressure on the pollock industry.

Cora Campbell, the Commissioner of the Alaska Department of Fish and Game and the ostensible lead author of the measure, said that kind of pressure on industry will provide the fastest relief.

“The things that can happen much more quickly than changes to federal regulations is changes to industry agreements,” Campbell said after the meeting. “And that’s why you saw the Council talking with industry, telling industry the changes that we’d like to see to industry agreements, because that is the way we can most immediately affect savings.”

The Council’s analysis aimed to tackle bycatch in several ways. First, by rolling Chinook and chum salmon bycatch measures into a single policy. When existing chum and Chinook rules conflict, the rules governing Chinook would take precedence.

The second part of the analysis would give pollock fishermen further incentive to avoid catching any salmon species; incentives the Council tweaked to be more restrictive on vessels that consistently catch the most salmon.

“We’ve seen some vessels do very well at doing better on bycatch and some vessels have not done as well,” Campbell said. “One of the things that industry heard loud and clear from the Council is that is not acceptable. We expect all vessels to be doing everything that they can, and that they need to go back and look at their agreements and find a way to deal with those vessels that we call outliers … those vessels that are doing significantly worse [with regard to salmon bycatch] than everybody else.”

Part of the incentive tweaks would also require relatively new devices on pollock trawl nets that exclude salmon.

Also in the analysis was a shift of the dates for the pollock fisheries. Data presented to the Council showed that fishermen are best able to avoid salmon by fishing early in the season. Accordingly, the analysis looks at shifting the start date for the Bering Sea pollock “B season” to June 1, and could shorten the pollock season by as much as a month by closing as early as mid-September. Options to close on October 1 and mid-October remain on the table.

The hard cap for king salmon remained at 60,000 fish, but Commissioner Campbell said the performance standard, set around 47,591 fish, is the figure “the industry manages to.” Part of the analysis ordered Saturday would reduce that number during years of weak king salmon runs (defined as an abundance below 500,000 fish) by 25 to 60 percent.

The meeting didn’t leave industry representatives happy, nor were local fishermen given the tightened restrictions, low hard caps, or emergency closures they had called for. Outgoing Council Chair Eric Olson, who was presiding over his final meeting after nearly a decade on the Council, said the crisis state of Chinook salmon means the task before future Councils could require drastic measures.

“It’s not incumbent on us to come up with a program that the industry has to agree with 100 percent,” Olson said. “The makeup of the Chinook salmon resource has been drastically changed, and it’s not out of question, in my view, to fundamentally change the program that we have.”

The Council is preparing for its final meetings in Nome Monday, including “staff tasking” that sets schedules for just how quickly parts of the analysis could be implemented. That could ultimately lead to significant lag between Saturday’s recommendations and actual in-the-field implementation.

The North Pacific Fisheries Management Council reconvenes for another meeting in Anchorage this October.